The

cover review in last Sunday's NYT Book Review was of Francis Fukuyama's new book, "America at the Crossroads." In this book, Fukuyama cites his attandance at a 2004 lecture by Charles Krauthammer as the starting point for his disillusionment with neo-conservatism, at least with what neo-coservatism has become in America today.

On the following Tuesday, Krauthammer published his rebuttal (to Fukuyama, not to the review) under the headline "

Fukuyama's Fantasy." He was not kind:

It was, as the hero tells it, his Road to Damascus moment. There he is, in a hall of 1,500 people he has long considered to be his allies, hearing the speaker treat the Iraq war, nearing the end of its first year, as "a virtually unqualified success." He gasps as the audience enthusiastically applauds. Aghast to discover himself in a sea of comrades so deluded by ideology as to have lost touch with reality, he decides he can no longer be one of them. . . .

I happen to know something about this story, as I was the speaker whose 2004 Irving Kristol lecture to the American Enterprise Institute Fukuyama has now brought to prominence. I can therefore testify that Fukuyama's claim that I attributed "virtually unqualified success" to the war is a fabrication.

I am normally not inclined to delve too deeply into the sectarian sqabbles between the Shia and the Sunnis of the neo-conservative religion. But, since Krauthammer oblging provided

a link to his speech, I decided to go read it.

Krauthammer is right. At no point in the speech did he say that the war in Iraq was an unqualified success, and he did acknowledge that "[i]t may yet fail." But, for all that, I can understand what left Fukuyama "aghast" at the speech, for it articulated a theory of international relations that, if accepted, would not only justify other such wars, but make them inevitable.

As the speech makes clear from the very outset, Krauthammer is giddily ga ga over American military power:

On December 26, 1991, the Soviet Union died and something new was born, something utterly new--a unipolar world dominated by a single superpower unchecked by any rival and with decisive reach in every corner of the globe.

This is a staggering new development in history, not seen since the fall of Rome. It is so new, so strange, that we have no idea how to deal with it. Our first reaction--the 1990s--was utter confusion. The next reaction was awe. When Paul Kennedy, who had once popularized the idea of American decline, saw what America did in the Afghan war--a display of fully mobilized, furiously concentrated unipolar power at a distance of 8,000 miles--he not only recanted, he stood in wonder: "Nothing has ever existed like this disparity of power;" he wrote, "nothing. . . . No other nation comes close. . . . Charlemagne’s empire was merely western European in its reach. The Roman empire stretched farther afield, but there was another great empire in Persia, and a larger one in China. There is, therefore, no comparison."

With that as a starting point, Krauthammer asks, and proceeds to try to answer the question: "What do we do? What is a unipolar power to do?"

He starts by rejecting Isolationism "because it is so obviously inappropriate to the world of today--a world of export-driven economies, of massive population flows, and of 9/11, the definitive demonstration that the combination of modern technology and transnational primitivism has erased the barrier between 'over there' and over here. "

He then moves on to the object of his greatest contempt: Internationalism, which he precedes with the epithet "liberal" (i.e. it is not just Internationalism, but "

Liberal Internationalism"). The first of his ground is Internationalism's naivete:

The Clinton administration negotiated a dizzying succession of parchment promises on bioweapons, chemical weapons, nuclear testing, carbon emissions, antiballistic missiles, etc.

Why? No sentient being could believe that, say, the chemical or biological weapons treaties were anything more than transparently useless. Senator Joseph Biden once defended the Chemical Weapons Convention, which even its proponents admitted was unenforceable, on the grounds that it would “provide us with a valuable tool”--the “moral suasion of the entire international community.”

Moral suasion? Was it moral suasion that made Qaddafi see the wisdom of giving up his weapons of mass destruction? Or Iran agree for the first time to spot nuclear inspections? It was the suasion of the bayonet. It was the ignominious fall of Saddam--and the desire of interested spectators not to be next on the list. The whole point of this treaty was to keep rogue states from developing chemical weapons. Rogue states are, by definition, impervious to moral suasion.

But the real nub of his complaint is that Internationalism's effect, and perhaps its very puuprose, is to constrain the American power of which he is so proud. Krauthammer points out that Internationaism as practiced by the Clinton Administration was not afraid to use American power. It was only afraid to use it in pursuit of "the raw national interest":

[W]hen liberal internationalism came to power just two years [after the first Gulf War] in the form of the Clinton administration, it turned almost hyperinterventionist. It involved us four times in military action: deepening intervention in Somalia, invading Haiti, bombing Bosnia, and finally going to war over Kosovo.

How to explain the amazing transmutation of Cold War and Gulf War doves into Haiti and Balkan hawks? The crucial and obvious difference is this: Haiti, Bosnia and Kosovo were humanitarian ventures--fights for right and good, devoid of raw national interest. [Emphasis in original]. And only humanitarian interventionism--disinterested interventionism devoid of national interest--is morally pristine enough to justify the use of force. The history of the 1990s refutes the lazy notion that liberals have an aversion to the use of force. They do not. They have an aversion to using force for reasons of pure national interest.

And by national interest I do not mean simple self-defense. Everyone believes in self-defense, as in Afghanistan. I am talking about national interest as defined by a Great Power: shaping the international environment by projecting power abroad to secure economic, political, and strategic goods. Intervening militarily for that kind of national interest, liberal internationalism finds unholy and unsupportable. It sees that kind of national interest as merely self-interest writ large, in effect, a form of grand national selfishness.

Krauthammer argues that this "aversion" to "projecting power abroad to secure economic, political, and strategic goods" stems from what he later describes as a "woolly" idealism; a desire to "remake the international system in the image of domestic civil society." To do this, he notes:

[Y]ou have to temper, transcend, and, in the end, abolish the very idea of state power and national interest. Hence the antipathy to American hegemony and American power. If you are going to break the international arena to the mold of domestic society, you have to domesticate its single most powerful actor. You have to abolish American dominance, not only as an affront to fairness, but also as the greatest obstacle on the whole planet to a democratized international system where all live under self-governing international institutions and self-enforcing international norms.

Krauthammer much prefers "Realism" precisley becuase "Realism recognizes the fundamental fallacy in the whole idea of the international system being modeled on domestic society."

First, what holds domestic society together is a supreme central authority wielding a monopoly of power and enforcing norms. In the international arena there is no such thing. Domestic society may look like a place of self-regulating norms, but if somebody breaks into your house, you call 911, and the police arrive with guns drawn. That’s not exactly self-enforcement. That’s law enforcement.

Second, domestic society rests on the shared goodwill, civility and common values of its individual members. What values are shared by, say, Britain, Cuba, Yemen and Zimbabwe--all nominal members of this fiction we call the “international community”?

. . .

Hence the realist axiom: The “international community” is a fiction. It is not a community, it is a cacophony--of straining ambitions, disparate values and contending power.

What does hold the international system together? What keeps it from degenerating into total anarchy? Not the phony security of treaties, not the best of goodwill among the nicer nations. In the unipolar world we inhabit, what stability we do enjoy today is owed to the overwhelming power and deterrent threat of the United States.

But, for Krauthammer, even Realism falls short and it does so becuase it has no aspirational underpinnings beyond the will to power:

For most Americans, will to power might be a correct description of the world--of what motivates other countries--but it cannot be a prescription for America. It cannot be our purpose. America cannot and will not live by realpolitik alone. Our foreign policy must be driven by something beyond power. Unless conservatives present ideals to challenge the liberal ideal of a domesticated international community, they will lose the debate.

It is from this that Krauthammer's vision of "Democratic Globalism" -- or more accuartely "Democratic Realism" -- emerges. Stated baldly, what Krauthammer is recommending is the relentless use of American power in pursuit of freedom and democracy: "a foreign policy that defines the national interest not as power but as values, and that identifies one supreme value, what John Kennedy called "the success of liberty." As President Bush put it in his speech at Whitehall last November: "The United States and Great Britain share a mission in the world beyond the balance of power or the simple pursuit of interest. We seek the advance of freedom and the peace that freedom brings."

But even Krauthammer cannot entirely buy this theory, for even he has to recognize that there are limits. We cannot, even with all our power make everyone free and democratic. So we have to have "criteria" for deciding when to go to war in defense or pursuit of freedom and when not to:

The danger of democratic globalism is its universalism, its open-ended commitment to human freedom, its temptation to plant the flag of democracy everywhere. It must learn to say no. And indeed, it does say no. But when it says no to Liberia, or Congo, or Burma, or countenances alliances with authoritarian rulers in places like Pakistan or, for that matter, Russia, it stands accused of hypocrisy. Which is why we must articulate criteria for saying yes.

Where to intervene? Where to bring democracy? Where to nation-build? I propose a single criterion: where it counts.

Call it democratic realism. And this is its axiom: We will support democracy everywhere, but we will commit blood and treasure only in places where there is a strategic necessity--meaning, places central to the larger war against the existential enemy, the enemy that poses a global mortal threat to freedom.

There is a lot in Krauthammer's critiques of Isolationism, Liberal Internationalism and Realism that is perceptive, although very little that is actually new. But his proposed solution would be just silly if it weren't so dangerous.

What do you get when you enlist violence or force in the aid of furthering an ideal? You get jihad. Oh sure, the goal of Krauthammer's jihad is to spread an ideal we believe in, and from which we fervently believe others would benefit. But Osama bin Laden no doubt feels the same way about the goals of his jihad. Using force to promote and propagate an ideal is what jihad is all about.

Among the many things Krauthammer gets wrong is his characterization of the American people. The BIG lie that we invaded Iraq to promote freedom and democracy. We did no such thing. The invasion of Iraq was promoted and sold as a necessary act of self-defense -- the quintessential "realpolitik" rationale for the use of force. Does anyone, Charles Krauthammer included, really believe that the American people could have been sold on invading Iraq to promote freedom and democracy?

Americans are ready, willing and able to fight, and to keep fighting, so long as they believe the fight is an effort to

defend America's national interest. Every war we have fought and of which we remain proud today was a war in

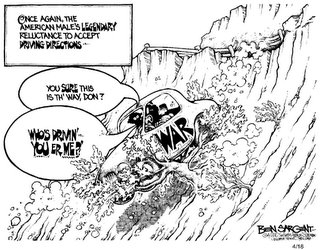

defense of something: The Revolution, the War of 1812, the Civil War, the Second World War, the Gulf War and the war in Afghanistan. The wars about which we are ambivalent are those we won but which were, at bottom wars of aggression, although decked out with such "ideals" as "manifest destiny" and "the white man's burden": the Indian Wars, the Mexican War and the Spanish-American War. The wars of which we are most ashamed are those that were sold to us as being defensive but which turned out to be no such thing: Vietnam and Iraq. Much to Krathammer's dismay, perhaps, Americans are not willing to go to war for propagate ideals. Thank God.

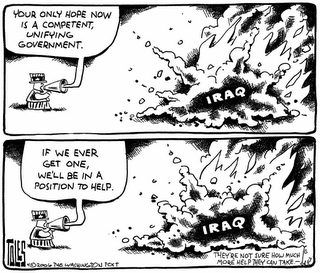

But, let's ignore that and look at Krauthammer's prescription for when we should use force. "We will support democracy everywhere, but we will commit blood and treasure only in places where there is a strategic necessity--meaning, places central to the larger war against the existential enemy, the enemy that poses a global mortal threat to freedom."

Talk about "woolly"! What does that mean? If we accept that formulation, should we or should we not have invaded Iraq? Should we or should we not invade Iran? North Korea? Sudan? Rwanda? The trick to using power is to know where and when, and suggesting that we should use it only against "the existential enemy, the enemy that poses a global mortal threat to freedom" is of little help. Who, and more importantly today,

where is that enemy?

Even Krauthammer seems confused about this. He claims "the existential enemy" today is "Arab-Islamic totalitarianism." But I doubt if even he really believes that characterization. Arab-Isalmic totalitarianism is alive and well in varying degrees everywhere in the Middle East. In pursuit of freedom, are we going to invade Iran? Syria? Eqypt? Palestine?

Saudi Arabia? Of course not, and the reason for this is that "Arab-Isalmic totalitarianism" is not the issue. What Krauthammer wants to fight -- defeat -- are people lke Osama bin Laden. But, he can't find them. We have all of this power, Krauthammer seemes to be saying, and we have to use it somewhere or what's the use of having it. The fact that the

real enemy is not susceptible to that that kind of power, and indeed feeds off of our efforts to use it, seems utterly lost on our commentator.

The only school of political thought worthy of the name "thought" is Realism. And, any realism worthy of that name recognizes (a) that there are limits to what can be accomplished by force and (b) that uninteneded and usually unpleasant consequences almost inevitably flow from such use. As such, the realist argues that force should be used

only if there is no other way to

protect the national interest. In some cases, the threat to the national interest is so palpable and direct that the need to use force becomes obvious. I would put WWII, perhaps Korea, Kuwait, and Afghanistan in this category. But in most cases, deciding whether to use force requires a much more nuanced sense of where the "national interests" lie and whether force will be effective in protecting those interests than our friend Krauthammer (and the neo-cons generally) seem to recognize. For instance, promotong stability in the world's troubled places is in our national interest, and in some cases (e.g. the Balkans) using military power to try to achieve that goal may be worthwhile. But that is a dicey prospect. If we succeed (e.g. the Balkans) we have made the world a bit safer. If we fail, (e.g. Somalia) we actually make the world more dangerous. So, such efforts should be undertaken, if at all, only when there is a high likelihood of success and when there will be other people to blame (e.g. allies) if we fail. It is in this sense that the "international legitimacy" of which Krauthammer is so contemptuous is so important to the Realist. No one questions America's right to act unilaterally where necessay to

protect its national interests. Ironically, though, where our national interests are clearly at stake, America is rarely, if ever, if forced to act alone. It is only where the tie to our national interests gets murky or where the effort appears more like an effort to promote rather than protect our national interests that we have trouble. And, I would submit, that is exactly the sort of case in which the Realist would think long and hard on the question of whether to proceed.

International relations, especially as it relates to the question of force, is not susceptible to the sorts of one-sentence prescriptions Krauthammer offers. It is complicated and all three of the schools of thought he describes play a role. I agree that "classical isolationism" is no longer viable (if it ever was), but even isolationism has a role to play in the sense that it argues we should not get involved overseas, especially militarily, unless we are sure such involvement necessary to protect our national interests. Internationalism also plays a role, since the support of allies makes it both more likely that we will succeed and less likely that we will become an object of contempt or hatred if we fail. Internationalism thus allows us to attempt things, like the Balkan intervention, that we would have been well advised to avoid had we been forced to go it alone. And realism plays a role as well, in the sense that it tells us that we rather thean the international community are the final arbiters of when we need to take action to protect our national interests.

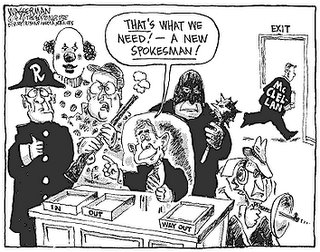

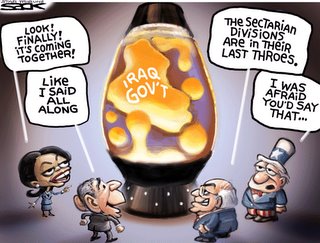

Shiite Drops Bid to Keep Post as Premier (NYT)

Shiite Drops Bid to Keep Post as Premier (NYT)

Iraq Breaks Impasse on Government (LAT)

Iraq Breaks Impasse on Government (LAT) Bin Laden Says West Is Waging War Against Islam (NYT)

Bin Laden Says West Is Waging War Against Islam (NYT)