Tuesday, February 28, 2006

Who Says You Can't Have It All?

"'Women today expect more help around the home and more emotional engagement from their husbands,' Wilcox says. 'But they still want their husbands to be providers who give them financial security and freedom.'"

Well I'll be! Who'd have thunk that?

Monday, February 27, 2006

Democracy and Freedom Are Not The Same Things

This is not to say democracy is a cure-all. It is also not to say that the peril these democracies face, from terrorist insurrection or ethnic or religious feuding, isn't grave. Nor, finally, is it to say that the "Hitler scenario" can be excluded in a democratizing Middle East; that possibility is always present, especially among nascent democracies.I don't really have a better idea. However, I think it is important to recognize that the editorial -- as does most of the writing and rhetoric around this topic -- conflates two different concepts. What we really want to spread is not so much democracy as it is "freedom." While we tend to think of democracy and freedom as being synonymous, they are not. Democracy is simply a process by which leaders are chosen. Freedom, on the other hand, is the substance of daily life: freedom of speech, press, religion and association; freedom from unreasonable governmental intrusion into our daily lives; and, the corollary of all of those: tolerance for people whose beliefs, preferences, and (within limits) practices differ from our own. It is this tolerance rather than the mechanisms used to select leaders that tends to make countries peaceful.

But democracy also offers the possibility of greater liberalism and greater moderation, possibilities that have been opened with the courageously pro-American governments of Hamid Karzai, Jalal Talabani and Saad Hariri. And as we stand with them, it seems to us that America's bets are better placed promoting democracies--even if some of them succumb to illiberal temptations--than acceding to dictatorships, which already have.

Or does someone have a better idea?

As the middle east is proving, over and over again, the fact that people are free to vote is no guarantee that the vote will result in either freedom or tolerance. Quite to the contrary. Elections in the middle east seem today to be more about legitimizing a tyranny of the majority over the minority. A tyranny is no less tyrannical because the tyrants were freely elected. And, it is no less a threat to its neighbors.

The fact that there have been free elections in the middle east is not a bad thing, of course. But it does not warrant the optimism it seems to engender in us. Elections are, in the end, relatively easy to set up. They are entirely mechanical. The essential -- but very much harder part -- is for the society to develop that commitment to tolerance that is the essential underpinning of what we refer to as freedom. Without that, democracy is simply another path to tyranny. And regardless of the mechanism used to invest it with power, a tyranny rooted in hatred of others is a threat to its neighbors.

Sunday, February 26, 2006

Some Thoughts On The Future Of Abortion

In the near term, the war will continue to be waged primarily in the courts, and, given the recent changes in its composition, the "new" Supreme Court can be expected to be more tolerant of procedural restrictions on abortion. But, for however long it is possible to do so, the Court will avoid directly addressing either Roe itself or the marvelously plastic "undue burden" standard articulated by O'Connor in Casey. This approach has already been used in the Roberts' Court's first abortion decision, Ayotte v. Planned Parenthood, where the Court managed to (unanimously!) reverse a lower court holding that a New Hampshire parental notification law was unconstitutional without ever reaching either Roe or the undue burden standard.

The partial birth abortion case recently accepted by the Supreme Court seems likely to follow the same pattern. The Supreme Court almost certainly did not take this case in order to agree with the three lower appellate court decisions holding the federal partial birth abortion ban to be unconstitutional. But the case does not require reconsideration of either Roe or the undue burden standard. In fact, it could be that the Supreme Court's problem with the lower court decisions has nothing to do with abortion at all.

At issue is a federal statute that is essentially indistinguishable form a state (Nebraska) statute that was struck down in 2000 in a 5-4 decision in Sternberg v. Carhart. The state statute presented a "pure" abortion decision, since the power of the states to regulate abortion is unquestioned except as limited by Roe and Casey. But a federal statute presents an intriguing preliminary question: what gives Congress the power to regulate abortion? The federal act is based on Congress' power to regulate interstate commerce. But, apart from the anomaly of the medical marijuana case, the Court has been increasingly hostile in recent years to claims that the commerce power reaches activities with no discernible actual impact on commerce between the states. In short, what everyone is assuming is an abortion case might well turn out to be a commerce clause case.

Even if the Court does reach the abortion question, though, it is clearly possible for the Court to uphold a partial birth abortion ban without reaching even the undue burden standard, much less Roe itself. After all, the only issue actually presented is one particularly gruesome procedure that is rarely used, that is even more rarely medically necessary, and that is used only in the second trimester or later when the Roe decision itself holds that the state's interests in protecting the unborn are in equipoise with the privacy interests of the mother. Under such circumstances, it would be very easy for the Court to conclude that prohibiting this procedure does not create an "undue burden" on women's privacy interests even if the majority of the Court believes that the undue burden standard, or even Roe itself, is wrong. Given the extreme care with which the Court can be expected to proceed in this most controversial of areas, I find it very hard to believe that it will issue a ruling that is any broader than is absolutely necessary to deciding the case.

Eventually, of course, the Court will be presented with a case that makes it impossible to avoid Roe. At present, the South Dakota statute seems likely to present this case, but even if not, a state statute barring essentially all abortions will inevitably come before the Court. When that occurs, I think the abortion foes are likely to be severely disappointed, perhaps even entirely disillusioned. It is easy to be doctrinaire on this issue when you are not on the Court. It is even easy to be doctrinaire when you are on the Court but know that your vote doesn't really matter since you are in the minority. But when it comes right down to it, I do not believe there will ever be five Justices who are willing to allow states to entirely abrogate a right that has become so deeply enmeshed in American law, that is in in its general outlines supported by a large majority of the American people, and that provides thousands of women each year with a choice other than that between bearing unwanted children and back-alley abortions.

Once that happens, and perhaps even before, I think both sides will come to understand that the legal issue is actually getting in the way. "Abortions should be legal, safe and rare," quoth Hillary. We may never get to the point of consensus on the first of these points, but even the Right would agree that, if there are to be abortions they should be safe and even the most ardent Leftist would agree that we should do whatever we can to minimize the number of abortions that occur.

In a NYT Op-Ed piece published last month, William Saletan eloquently presented the pro-choice case for this approach. Portions of this are reproduced below:

How to accomplish this -- how to reduce or eliminate the number of abortions by reducing or eliminating the number of unplanned pregnancies -- will itself be contentious, with the Right arguing for "abstinence only" and the Left arguing that the only answer is contraception. But that debate, at least, will be over the tactics as to how best to pursue a common goal -- a debate that would be far less corrosive than the one we are having today.EVERY year, on the anniversary of Roe v. Wade, pro-lifers add up the fetuses killed since Roe and pray for the outlawing of abortion. And every year, pro-choicers fret that we're one Supreme Court justice away from losing ''the right to choose.'' One side is so afraid of freedom it won't trust women to do the right thing. The other side is so afraid of morality it won't name the procedure we're talking about.

It's time to shake up this debate. It's time for the abortion-rights movement to declare war on abortion.

* * * *

The [Left's] problem is abortion -- the word that's missing from all the checks you've written to Planned Parenthood, Naral Pro-Choice America, the Center for Reproductive Rights and the National Organization for Women. Fetal pictures propelled the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act and the Unborn Victims of Violence Act through Congress. And most Americans supported both bills, because they agree with your opponents about the simplest thing: It's bad to kill a fetus.

They're right. It is bad. I know many women who decided, in the face of unintended pregnancy, that abortion was less bad than the alternatives. But I've never met a woman who wouldn't rather have avoided the pregnancy in the first place.

The lesson of those decades is that you can't eliminate the moral question by ignoring it. To eliminate it, you have to agree on it: Abortion is bad, and the ideal number of abortions is zero.* * * *

A year ago, Senator Hillary Clinton marked Roe's anniversary by reminding family planning advocates that abortion ''represents a sad, even tragic choice to many, many women.'' Some people in the audience are reported to have gasped or shaken their heads during her speech. Perhaps they thought she had said too much.

The truth is, she didn't say enough. What we need is an explicit pro-choice war on the abortion rate, coupled with a political message that anyone who stands in the way, yammering about chastity or a ''culture of life,'' is not just anti-choice, but pro-abortion.

Bode Bush: The Worst President Ever?

In a sense, though, the comparison is unfair -- to Bode. For all his considerable failings and failures, Bode is at least in no danger of being found to have been the worst skier in history. George, on the other hand, could very well be history's worst president.

I am nowhere near a good enough student of the Presidency to rate Presidents, especially those prior to the turn of the century. But modern Presidents seem to have fallen into five categories: those who were truly great (Roosevelt); those who had a mixed record of accomplishment but had the good sense not to screw up the energetic, peaceful times over which they presided (Clinton); those whose significant accomplishments were overshadowed in the end by horrible failures (Johnson); those who accomplished little but at least did no significant harm (Eisenhower); and those who failed to act effectively in the face of impending crisis but who probably cannot be fairly blamed for causing the crisis itself (e.g. Hoover).

Bush, though, seems to be in a class by himself. He seems to combine the very worst of all his immediate predecessors. His foreign policy is worse than Johnson's. His domestic policy is worse than Hoover's. His (or at least his Administration's) honesty and respect for law are worse than Nixon's. And his overall ineptness is at least as bad as Carter's.

I cannot identify a single positive thing that Bush has done. Perhaps "No Child Left Behind" will eventually have good results, although the early returns are far from encouraging. But beyond that, everything I can think of is an unmitigated disaster.

Domestically he has given us tax cuts, a Medicare drug benefit, the Department of Homeland Security, NSA spying, an assertion of executive power that would make Nixon blush, and a polarization of the electorate that is probably unprecedented, at least in the last 100 years. The first two of these will pose unsustainable burdens on our children and will end up exacerbating the polarization of American society. The third is at best a bad joke and at worst a cure far worse than the disease. And the last two are unimaginably dangerous.

His international "accomplishments" are even worse. Like Johnson he embroiled us in a war that did not need to be fought and cannot be won. But unlike Johnson's war, Bush's now seems virtually certain to undermine the stability of an entire region of the world that is of critical strategic importance to the United States. In addition, he has brought us Abu Grahib, Guantanamo, black camps, extraordinary rendition, and acceptance, even encouragement of torture. All of this he did in the name of increasing American security. But can anyone deny that we are both far less secure and far less free today that we were even on September 10, 2001?

Is there anything positive that has come from this Administration? Is there a worse President in the last 100 years? Or ever?

Thursday, February 23, 2006

Overplaying The Anti-Abortion Hand

The goal of the law, of course, is to give the Supreme Court no alternative but to directly confront Roe v. Wade. Yet, it is almost inconcieveable that, when push comes to shove, a majortiy of the Supreme Court will vote to uphold such a law. The result, I suspect, will be a reaffirmation of the basic principle that underlies the 1973 decision: that there are limits on what the states can criminalize in this area.

Bears make money, bulls make money, pigs get slaughtered.

Thursday, February 16, 2006

A Cheney Resignation????

So, I was disgusted but not all that surprised to find that the lead stories in the e-mail versions of both the New York Times and the Washington Post were entitled, respectively "Silence Broken as Cheney Points Only to Himself" and "Cheney Says Shooting Was His Fault [subtitle]But He Stands By Decisions On Disclosure." Further, both of the Op-Ed pieces in the New York Times and on in the Wall Street Journal were devoted to this "story." As if Cheney's interview on Fox yesterday was THE most important thing to happen in the world.

While I didn't -- nor will I -- see the interview or read the transcript, the statements attributed to Cheney (even I can not completely avoid hearing about this incident) do him credit. He blamed no one but himself and appears to be genuinely anguished about it. The fact that anguish and blame-taking are not attributes one normally associates with our VP makes this confession seem all the more real and actually helps to humanize a man who has (with considerable justification) become the Great Satan of domestic politics.

But none of that is what led me to break my vow of silence on shotgun-gate. Rather it was two editorials, one by Bob Herbert at the New York Times and another by Peggy Noonan at the Wall Street Journall suggesting that this incident might be (in the case of Noonan) and should be (in the case of Herbert) the catalyst that leads Bush to jettison Dick Cheney.

Huh? What ARE these people smoking?

I guess I shouldn't be too categorical about this possibility. Washington is just too strange a place to say confidently that this or that could never happen. And the fact that two so diverse people as Herbert and Noonan came out with the same suggestion on the same day gives the conspiracy-theorist in me pause. Is it possible that this idea did not pop unbidden into each of their minds? Could both actually be tied to some "trial balloon" floated by someone powerful enough to actually get Cheney fired (e.g. Grover Norquist, or William Kristol or Pat Robertson)?

Or, could it be that the "birdie" whispering to Herbert an Noonan is actually Cheney himself? Is it Cheney who wants to quit and is looking for political cover?

That last is an interesting possibility, and would not be inconsistent with what we know of the personalities involved.

The idea that Bush would dump Cheney seems so far-fetched as to be almost laughable. Given the conventional wisdom regarding Cheney's role in the Administration, a report that Cheney was on the verge of dumping Bush would actually be more plausible. Moreover, even if Cheney isn't in charge, there is another problem: Bush doesn't fire people, since doing so is an implicit admission of error. And, admitting error, even implicitly, is something Bush just . . . does . . . not . . . do. Oh sure, he did finally fire Brownie and he did finally "fire" Harriet Miers. But those are the exceptions that prove the rule: it took cataclysms of opposition (and in Brownie's case, at least, incompetence) so great as to threaten Republican control of government to persuade him to cut his losses. And, neither of these people had anything like Dick's clout.

So, unless Herbert and Noonan are just out to lunch, the only possibility that makes any sense is that Cheney himself wants out. That's not impossible. For all of his hubris -- or perhaps because of it -- Cheney may have just gotten sick of the bullshit. One can almost imagine him saying to himself, "Ah Maureen and all of you other contemptible Lilliputians, go f#@k yourselves! I'm blowing this pop stand and going somewhere where I can make real money and have real power and where I don't have to put up with your prying, niggling little questions and constant griping. I'm going back to Haliburton. Oh, and getting paid $250K per shot to lambast all you idiots on the lecture circuit has some considerable appeal as well."

Hmmm. Stay tuned.

Tuesday, February 14, 2006

Maybe I'll Vote For DeWine After All

Here's his statement announcing his withdrawal. It is perhaps a bit histrionic, smacking more than a bit of Nixon's "You won't have Dick Nixon to kick around anymore." Still, a little of the independence, candor and integrity that made Hackett's candidacy exciting does come through:

Today I am announcing that I am withdrawing from the race for United States Senate. I made this decision reluctantly, only after repeated requests by party leaders, as well as behind the scenes machinations, that were intended to hurt my campaign.

But there was no quid pro quo. I will not be running in the Second Congressional District nor for any other elective office. This decision is final, and not subject to reconsideration.

I told the voters from the beginning that I am not a career politician and never aspired to be--that I was about leadership, service and commitment.

Similarly, I told party officials that I had given my word to other good Democrats, who will take the fight to the Second District, that I would not run. In reliance on my word they entered the race. I said it. I meant it. I stand by it. At the end of the day, my word is my bond and I will take it to my grave.

Thus ends my 11 month political career. Although it is an overused political cliché, I really will be spending more time with my family, something I wasn't able to do because my service to country in the political realm continued after my return from Iraq. Perhaps my wonderful wife Suzi said it best after we made this decision when she said "Honey, welcome home." I really did marry up.

To my friends and supporters, I pledge that I will continue to fight and to speak out on the issues I believe in. As long as I have the microphone, I will serve as your voice.

It is with my deepest respect and humility that I thank each and every one of you for the support you extended to our campaign to take back America, and personally to me and my family. Together we made a difference. We changed the debate on the Iraq War, we inspired countless veterans to continue their service by running for office as Democrats and we made people believe again. We must continue to believe.

Remember, we must retool our party. We must do more than simply aspire to deliver greatness; we must have the commitment and will to fight for what is great about our party and our country; Peace, prosperity and the freedoms that define our democracy.

Rock on.

Paul Hackett

The "machinations" he refers to were, reportedly, calls by Party leaders to his donors urging them to refuse to give him any more money.

The Democrats are so pathetic. Here was a guy that had the potential to breathe some life into an increasingly inanimate party, and they scuttled him in favor of Sherrod Brown.

Monday, February 13, 2006

Bush, Dole And Nixon

I was able to identify the exceptional year without much effort. But in several of the years in which a Bush, Dole or Nixon was running for President, I must admit to having had to resort to Wikipedia to figure out who the Vice Presidential candidates were.

If you are interested, the answers are posted in the Comments to this post.

Saturday, February 11, 2006

OK. Enuf Of This PR Shit! Gimme An Insurgent!

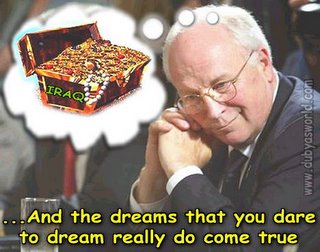

Cheney Assurances: Deja Vu All Over Again

Dick's at it again, assuring us that the President's policies are good for us. Last time it was Iraq's WMDs. This time it is taxes and deficits: Cheney Says New Unit Will Prove Tax Cuts Boost Revenue:

Dick's at it again, assuring us that the President's policies are good for us. Last time it was Iraq's WMDs. This time it is taxes and deficits: Cheney Says New Unit Will Prove Tax Cuts Boost Revenue: Vice President Cheney said Thursday night that the verdict is in before the Bush administration's new tax analysis shop has even opened for business: Tax cuts boost federal government revenue. . . . Cheney touted President Bush's recently announced proposal to create a tax analysis division as a move toward providing more evidence for the administration's side of the argument.The idea for a new tax analysis shop sounds familiar too, as does the fact that Cheney already knows what its conclusions will be. Remember the "Office of Special Plans" that Cheney, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz and Feith set up to "fix" what they believed to be the inability of exisiting intelligence agencies to "properly" analyze intelligence on Iraq? Gee, do you think there might be a pattern here?

As was true with Iraq, I certainly hope Cheney is right. But you'll excuse me if I take both his assurances and the output from the new tax shop with more than a bit of skepticism.

(Picture courtesy of Bush Humor)

Friday, February 10, 2006

Venting On The Cartoon Riots

First, Krauthammer points out the duplicitousness of both the outrage in the streets and the rhetoric of the apologists:

Have any of these "moderates" ever protested the grotesque caricatures of Christians and, most especially, Jews that are broadcast throughout the Middle East on a daily basis? The sermons on Palestinian TV that refer to Jews as the sons of pigs and monkeys?If you doubt the virulence of the Arabic press in this regard, take a tour of Palestinian Media Watch, and, of particular relevance, glance at these "cartoons" from the Palestinian Press. Then, ask yourself where the outrage over some comparatively playful jibes at Muslims comes from.

The real point of the column, though, is this:

It's so true. But, like most venting, it may well feel good but it ain't very productive. How are we to battle against the fear? Republish the cartoons (or redo whatever offends these nut cases)? Would that have any beneficial effect either in abating our fear or in mollifying the goof balls? No. It is like raging against the wind.The mob has turned this into a test case for freedom of speech in the West. The German, French and Italian newspapers that republished these cartoons did so not to inform but to defy -- to declare that they will not be intimidated by the mob.

What is at issue is fear. The unspoken reason many newspapers do not want to republish is not sensitivity but simple fear. They know what happened to Theo van Gogh, who made a film about the Islamic treatment of women and got a knife through the chest with an Islamist manifesto attached.

The worldwide riots and burnings are instruments of intimidation, reminders of van Gogh's fate.

The best option, of course, would be to ignore them. That's hard to do, obviously, when they are burning down embassies. But, we should try. The less attention the world pays to this type of stuff, the less of it there will be.

The Omniscient Onion

Well, if you had been a regular reader of The Onion (America's Finest News Source), you would not have been surprised, becuase you would have read this, from two years ago: "Fuck Everything, We're Doing Five Blades."

Given the Onion's obvious perspecacity, we should probabaly take serioulsy two reports that appear, respectively, in last week's and this week's editions: "President Creates Cabinet-Level Position To Coordinate Scandals" and "White House Debuts Iraq War Infomercial."

Now if only we can get them to start writing about stock prices!

Parody Is The Best Medicine

Note to Dick: Start a riot! He is making fun of your religion!

Thursday, February 09, 2006

The WSJ Sells Out

Judging by Monday's hearing, Senators of both parties are still hoping to stage a Congressional raid on Presidential war powers. And they hope to do it not by accepting more responsibility themselves but by handing more power to unelected judges to do the job for them. . . . What FISA boils down to is an attempt to further put the executive under the thumb of the judiciary, and in unconstitutional fashion. The way FISA works is that it gives a single judge the ability to overrule the considered judgment of the entire executive branch. In the case of the NSA wiretaps, the Justice Department, NSA and White House are all involved in establishing and reviewing these wiretaps. Yet if a warrant were required, one judge would have the discretion to deny any request. . . . [T]he President is accountable to the voters if he abuses surveillance power. Fear of exposure or political damage are powerful disincentives to going too far. But judges, who are not politically accountable, have no similar incentives to strike the right balance between intelligence needs and civilian privacy. This is one reason the Founders gave the judiciary no such plenary powers.There is so much nonsense in this that it is hard to know where to begin. But let's start with the Fourth Amendment:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.I will assume that the WSJ does not consider this to be an unconstitutional limitation on the President's war-making power. But if that is true, then whom, apart from the "unelected judiciary" does the WSJ suppose is charged with the responsibility for issuing the required warrants and for determining if probable cause exists? Congress? The Executive? No one? And, if it is the judiciary, how can one argue that the "unelected" status of federal judges somehow disqualifies them from making those determinations? The Constitution itself provides that federal judges are to be appointed, not elected, with the advice and consent of the Senate. So what exactly is this claim that FISA is unconstitutional because it places the decision of whether to allow such searches in the hands of unelected judges? It is an argument, in effect, that the Constitution itself is unconstitutional.

If one believes that the Forth Amendment means what it says (as one would suppose the WSJ would do) then what FISA actually does is to impose extra-constitutional limits, not on the executive, but on the judiciary by creating a single, special, secret (and by all accounts highly accommodating) court and then divesting all other federal courts of any jurisdiction to rule on any warrant requests that are alleged to implicate national security.

A second point. For the Journal to argue that the appropriate -- and apparently only -- check on the President's power is his "accountab[ility] to the voters [and] [f]ear of exposure or political damage" is to argue, in effect, that we do not need a Constitution or a judiciary. As no less a conservative icon than Justice Scalia has pointed out, the major purpose of the Constitution is to protect rights considered fundamental from the "tyranny of the majority" and the most important function of the courts is to tell the majority to "take a hike" when it oversteps the bounds imposed by the Constitution.

Third, the editorial appears to entirely miss the double irony in its position. As its editorials on the Roberts and Alito nominations make clear, the WSJ is an ardent devotee of the doctrine of "strict constructionism." Judicial "creation" of rights or powers that are not found in the literal language of the Constitution is anathema. Yet, in this case, the Journal is prepared to "find" a right of the President to conduct warrantless searches in the "penumbras" that the Journal discerns around the Constitutional provisions vesting executive power in the President and designating him as commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Moreover, it does this despite the fact that the President is also charged with the duty to see that the laws are faithfully executed and a Fourth Amendment that, on its face at least, would appear to make all warrantless searches illegal. And here is the other, even sweeter irony: To reach this conclusion, the Journal has to rely on a body interpretational of law made by that same "unelected judiciary" that it so scorns.

The final startling thing about the editorial is that it swallows, entirely uncritically, the Executive's claim that the scope of the eavesdropping program is strictly limited.

Far from being some rogue operation, the Bush Administration has taken enormous pains to make sure the NSA wiretaps are both legal and limited. The program is monitored by lawyers, reauthorized every 45 days by the President and has been discussed with both Congress and the FISA court itself.How, pray tell, does the WSJ know this? The "pains" the Administration has taken to make sure the program is legal is the very question being debated, so this much of the assertion is just ipse dixit. The real question revolves around the "pains" that have been taken to make sure that the eavesdropping is "limited." The facts that the program it is "monitored by lawyers", "reviewed" every 45 days by the President (even if true) hardly provides assurance that the program is actually limited to intercepting calls by or to "known" Al Queda operatives. The only basis we have for believing such a limitation exists is the assurance of the Executive itself. Yet, the whole point behind the Fourth Amendment (as well as FISA) is that assurances of reasonableness by the very people who want to conduct the searches can not be trusted. Those assurances need to be tested before a neutral arbiter: the unelected judiciary.

Therein lies the most disappointing thing of all about the editorial. The WSJ editorial page holds itself out as being committed to conservative principles. The hallmark of a conservative, however, at least one that has not slipped over into fascism, is skepticism of government. It is both sad and a bit frightening to see the WSJ so completely abandon this principle.

Lobbying Reform: A (Mostly) Pointless Ballet

Courtesy of the Encyclopedia Britannica, Kabuki is a:

Popular Japanese entertainment that combines music, dance, and mime in highly stylized performances. . . . The lyrical but fast-moving and acrobatic plays, noted for their spectacular staging, elaborate costumes, and striking makeup in place of masks, are vehicles in which the actors demonstrate a wide range of skills.Is that not an apt description of what is going on in Washington now regarding lobbyists?

It is very hard to believe that these efforts will actually make a difference. Will there be new rules? Sure. Will some sort of reporting and oversight functions be added? Probably. Will any of these "reforms" make any substantive difference? Not likely.

This effort seems remarkably similar to the periodic debate around campaign finance reform. Every decade or so we have a paroxysm of national angst of over the role money plays in election campaigns. This leads to editorials, press conferences, hand-wringing, righteous indignation, hearings and ultimately legislation. But it takes the political parties about a week after the new rules are established to find and implement new ways of doing the exact same things. And they inevitably succeed.

The same phenomenon occurs -- for the same reasons -- in our periodic crusades against Congressional influence peddling.

The incentives involved applying money to politics are enormous: money begets power, which begets more money, which begets more power, and so on. Laws are bad mechanisms for dealing with such incentives. They are, literally, sitting ducks. As soon as a given requirement is written down, armies of very smart people set about finding the loopholes or oversights or omissions (both intentional and inadvertent) that provide new routes to doing the same old things. The law is no more capable of protecting us from the influence money has on politics than the Maginot Line was capable of protecting France from Germany.

I do not mean to suggest that the periodic indignation and breast beating on these issues is totally useless. But their utility is entirely normative. Do not expect new rules to eliminate the problem. They won't. But the public angst does tend to remind the politicians that people care about this type of thing. And those periodic reminders do tend to keep the politicians -- well, at least most of them -- from going too far off the rails.

We cannot hope to legislate integrity any more than we can hope to legislate morality. In the end, we have to rely on the consciences of the people we elect, and punish at the polls (and in court in those rare cases in which prosecution becomes possible) those who betray that trust. Beyond that, the most we can do is provide the politicians with periodic reminders that we do care about honesty in government.

Monday, February 06, 2006

The Administration's Definition of "Limited"

Without the context, this article on the NSA eavesdropping program from yesterday's Washington Post would just be fascinating, outlining as it does some of the technical capabilities and practices of the NSA (in that regard, the merest tip of the iceberg I am sure). However, given the context, it is truly terrifying. It turns out there are no legal or policy-based limits on the eavesdropping program. The only limits are those posed by the capabilities of the 38,000 NSA employees and the computers they use. And even those "limits" are far, far smaller than anyone reading this blog would ever suspect.

It would be nice to believe that the Supreme Court -- or the law in general -- could put this genie back in the bottle. But that is a like counting on the nuclear non-proliferation treaty to control the spread of nuclear weapons. However much we might wish it were otherwise, the whole notion of a "private" communication, even among citizens, has become simply quaint. We have but two choices: quit communicating or accept the fact that the Government is probably intercepting the communication. The only battle worth fighting now is the one over what the government can do with the information it collects.

Long live the poisonous tree!

Gonzales On The NSA Eavesdropping Activities

Efforts to identify the terrorists and their plans expeditiously while ensuring faithful adherence to the Constitution and our existing laws is precisely what America expects from the president.Exactly right.

History is clear that signals intelligence is, to use the language of the Supreme Court, "a fundamental incident of waging war." President Wilson authorized the military to intercept all telegraph, telephone and cable communications into and out of the U.S. during World War I. The day after Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt authorized the interception of all communications traffic into and out of the U.S.I have no reason to doubt that this is true. However, the fact that things like this have been done before does not necessarily prove that they are lawful. After all, Roosevelt interned Japanese citizens and few today would argue that this was consistent with the Constitution.

The AUMF is not a blank check for the president to cash at the expense of the rights of citizens. The NSA's terrorist surveillance program is narrowly focused on the international communications of persons believed to be members or agents of al Qaeda or affiliated terrorist organizations. The terrorist surveillance program protects both the security of the nation and the rights and liberties we cherish.If only that were so.

A few points to consider:

- The acts attributed to Wilson and Roosevelt preceded passage of FISA. Thus, even if we were to concede that those were valid exercises of Presidential power, those precedents would have little to say about the present issue unless one is prepared to argue that the eavesdropping power is inherent in the Presidency and is beyond the power of Congress to regulate. But if that is the argument, then the AUMF itself is irrelevant and the Administration's reliance on it is a red herring.

- If the types of activities attributed to Wilson and Roosevelt are "a fundamental incident of waging war," and if the AUMF authorizes this Administration to use all such "incidents," then how is the AUMF anything but a "blank check"? Under this theory, Bush, like Wilson and Roosevelt, could intercept and monitor all communications traffic in and out of the United States.

- How do we know the NSA program is "narrowly focused?" At best we have to take the Administration's word for that, an Administration who's record is, shall we say, a bit spotty on the candor criterion. Moreover, the available evidence tends to belie that claim. As noted by Bob Herbert of the New York Times, "The National Security Agency sent so much useless information to the F.B.I. in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks that agents began to joke that the tips would result in more 'calls to Pizza Hut.' [T]housands of tips a month came pouring in, virtually all of them leading to dead ends or innocent Americans." Actually, though, the truth or falsity of this claim is really beside the point. The Administration does not claim that the eavedropping is lawful becuase it is "limited." To the contrary, it claims is that the Constitution imposes no limits (see Wilson and Roosevelt examples above) and that even if there are limits, the AUMF removes them.

Beirut Mob Burns Danish Mission Over Cartoons

Enough of the attempts at understanding and excuse. There is something fundamentally sick about a culture that produces -- over and over again -- this sort of mindless, hysterical violence.

What is wrong with these people?

More to the point, how do we deal with them?

Sunday, February 05, 2006

I'm Only A Social Liberal

The NYT's lead editorial today was entitled Will Your Money Last? It starts with the following very comment-worthy (and scary) factoid:

Americans spent more than they made in 2005, sending the personal savings rate into negative territory for the first time since 1933.In classic liberal style, the Times then goes on to argue that the government should do something about this situation. For the Times, it seems, the solution to every problem is more government. But as is often the case, the "cures" seem worse than the disease.

The Times offers three suggestions for government action, each one scarier than the last.

First, it suggests that since companies are increasingly turning away from defined benefit retirement plans toward defined contribution plans in which employees are responsible for managing their own retirement accounts, the companies should be required to provide employees with professional investment advice. At first blush, this suggestion seems harmless enough, but even here one has to ask "Who pays?" Professional financial advisors are no more inclined to work for free than are auto workers. Thus, requiring companies to provide such advice inevitably drives up the cost of the defined contribution plans. Regardless of who pays these costs in the first instance, the requirement to provide financial advice will inevitably tend to depress the value of the accounts: either it will reduce contributions made by employers or it will increase the costs the employees are required to pay for those accounts. Maybe the benefits would outweigh the costs. But shouldn't such decisions be up to the employees? Not all employees will need such advice and of those who do, many will not utilize it even if provided. Why should we require such employees to pay (one way or the other) for what they either do not need or do not want? Wouldn't it be better for the Company to put the money it would otherwise spend on financial advisers into the accounts and then let the employee decide whether and how much professional advice to get?

The Times' second suggestion is to require employees who leave a job to roll their 401(k)'s into IRAs rather than taking the cash. In most cases, this is clearly the wisest course and the tax code is loaded with disinecentives to taking money out of a retirement account early. But one can easily imagine a situation in which taking the cash would be justified. Should we deprive employees of that freedom just because in most cases a rollover would be wise?

Finally, -- and most scary of all -- the Times suggests that:

Government must help ensure that retirees do not outlive their money. For many retirees, it would be prudent to convert savings into an annuity that would guarantee a stream of income for life. But the average 401(k) balance for people in their 60's is about $140,000, and financial companies cannot profitably offer annuities for such relatively small sums. Research suggests that the government could provide annuities for 401(k) savers who have $50,000 to $200,000 at modest cost.I have no idea what the Times considers to be a "modest cost." I also have no idea what sort of a monthly benefit such a federally subsidized annuity would pay. But this proposal sounds an awful lot like social security, and the costs of that program can hardly be described as "modest." As with social security, the only way to cover those costs in through taxes on those still working.

As a replacement for social security, what the Times is proposing is something very similar to Bush's private accounts: the worker puts his FICA payments into a private account and, if the private account is insufficient to pay some minimum lifetime benefit after retirement, the government makes up the difference. If that is what the Times is advocating, I am all for it. See this and this. But given the Times' adamant opposition to Bush's social security "reforms", I can only assume that this proposal would be in addition to social security. If that is the case, the proposal is hardly even responsible, much less practical.

The Times ends its editorial with the following:

It simply makes no sense, socially or economically, for each person to increasingly bear the risks of financing old age when that risk is more efficiently borne on the much broader shoulders of Washington and corporate America. What America needs are leaders who understand that asking ordinary citizens to assume ever-greater risks is not the path to greater security.I do not disagree that government should guarantee people some minimal level of income in retirement. However, one also has to realize two things. First, "Washington" and "corporate America" are not entities separate from the people who comprise them (taxpayers in the case of Washington; employees and stockholders in the case of companies. Thus, the "shoulders" onto which the Times proposes to place the risk of inadequate savings are the shoulders of the very people they are trying to protect from risk. Second, it is impossible to eliminate risk. It is only possible (as the Times seems to recognize) to transfer it from one person or group to another. When we do this, we deprive both the transferor and the transferee of a significant degree of their own freedom.