Our goal in life should NOT be to arrive safely at the grave in an attractive and well preserved body. We should rather aim to skid in sideways, chocolate in one hand, martini in the other, totally worn out and screaming "WOO HOO what a ride!

Monday, October 31, 2005

Living Large

And So It Begins

From People for the American Way:

BUSH PUTS DEMANDS OF FAR-RIGHT ABOVE INTERESTS OF AMERICANS WITH HIGH COURT NOMINATION OF RIGHT-WING ACTIVIST ALITO.It's hard to see how this is good news for the Country.

PFAW will wage massive national effort to defeat nominee who would dramatically shift balance of Court.

Update: From Planned Parenthood:

Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA) today called for the Senate to reject President Bush's nomination of Samuel Alito, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, to replace retiring Justice Sandra Day O'Connor.From NARAL:

"Judge Alito would undermine basic reproductive rights, and Planned Parenthood will oppose his confirmation," said Karen Pearl, interim president of PPFA. "It is outrageous that President Bush would replace a moderate conservative like Justice O'Connor with a conservative hardliner. There is no room on the court for someone with a judicial philosophy that places at risk the rights, freedoms, and liberties that Americans hold dear."

NARAL Pro-Choice America announced its opposition to President Bush’s nomination of Samuel Alito, Jr. to replace retiring Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. In choosing Alito, President Bush gave into the demands of his far-right base and is attempting to replace the moderate O’Connor with someone who would move the court in a direction that threatens fundamental freedoms, including a woman’s right to choose as guaranteed by Roe v. Wade.

Samuel Alito’s record reveals troubling elements that place him well outside the American mainstream

If you're interested in reading a lot more of these knee-jerk reactions, the Washingtomn Post Supreme Court Blog is compiling them.

Sunday, October 30, 2005

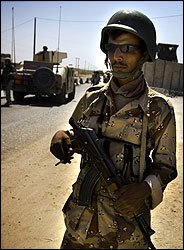

Getting The Iraqis To "Stand Up"

When the article talks about a lack of armor, it is not talking about tanks. It is talking about armored personnel carriers and body armor. How can we expect the Iraqis to stand up in a war of ambush and IEDs without such basic protections, especially when the people they are supposed to replace DO have them. Under such circumstances, the wonder is that they fight at all.

The explanation is even more troubling:

The Army unit in charge of equipping and training the Iraqis, the Multi-National Security Transition Command-Iraq, said it was trying to replace much of the Iraqi fleet with new armored trucks.

But it has largely restricted its shopping to American companies that are still swamped by orders for American troops. The unit's biggest initiative, to give the Iraqis 1,500 armored Humvees, will not begin until December, and most will not be built until next summer, military and company officials said.

The Pentagon still has only one contractor in Ohio armoring the Humvees, and a backlog of orders for American troops that dates to the early months of the war has forced the Iraqi troops to the end of the line.

"We're competing with the Army on that," said Lt. Gen. David H. Petraeus, who led the transition unit until last month.

I'm not suggesting that we should stop equipping our own troops in order to equip the Iraqis. But, it does seem to me that three plus years after the war began, we would have found a way to meet the needs of both armies.

If it is true that we can't leave until the Iraqis can take responsibility for fighting the war themselves, then we damn sure ought to be bending every effort toward at least getting them the equipment they need to have a chance.

Plame/Wilson/Libby/Rove Redux

The main thrust of the comments was disbelief that I could say outing Valerie Plame was not a crime. This comment comes, I think, from the different meanings of the term "crime". (Do I sound Like Bill Clinton?)

In common parlance, we tend to call actions we think of as despicable "crimes," as in the statement "That's a crime!" I myself used it in that sense in the post on Frank Rich's Op-Ed piece in the October 24 NYT. Rich described a wag-the-dog scenario in which Rove/Libby/Cheney et al. had quite self-consciously manufactured evidence for going to war in Iraq in order to assure a Republican victory in the 2002 mid-term elections (Rove's motivation) and to further the neoconservative wet dream of "mak[ing] the Middle East safe for democracy (and more secure for Israel and uninterrupted oil production)" (Libby/Cheney's motivation). In Rich's view:

Mr. Libby's and Mr. Rove's hysterical over-response to Mr. Wilson's accusation, [was the result of the fact that Wilson] scared them silly. He did so because they had something to hide. Should Mr. Libby and Mr. Rove have lied to investigators or a grand jury in their panic, Mr. Fitzgerald will bring charges. But that crime would seem a misdemeanor next to the fables that they and their bosses fed the nation and the world as the whys for invading Iraq.I allowed that, if this were true, that would be "a real crime."

But, when it comes to indictments, the word "crime" has a much more technical meaning: it is that set of acts and states of mind that the law says is criminal and nothing more or less. It was in this sense that I was using the term when I argued that outing Valerie Plame/Wilson was not "a crime." I did not intend to suggest the outing was reasonable or appropriate or anything of the kind. What I was saying was that, however despicable the outing and the motivations behind it may have been, Fitzgerald was not going to be able to indict Libby or Rove for the outing itself, because he was not going to be able to prove that Rove or Libby knew Plame was a covert operative and knew that the CIA was then trying to keep her CIA employment a secret. And, without such knowledge, telling reporters that Plame worked for the CIA was not "a crime."

And therein lies the problem I see in the Libby indictment. When a person does something that is despicable but not technically a crime, we have a tendency to want to get him for something that is a crime (in the technical sense) in order to punish him for the act that is really at issue but is not legally punishable. It is this motivation that led us to go after Al Capone on tax evasion and it is this same "rough sense of justice" that leads us to applaud the indictment of Libby on perjury and obstruction of justice. We are not, I submit, angry at Libby for lying about who told him Valerie Plame worked for the CIA. That is venal and contemptible and cowardly, but, if he had been lying about something trivial (like Clinton's affair with an intern), my guess is we would feel a lot less gleeful about the fact that he was indicted. The things we are really angry about are the lies that contributed to getting us into war and the subsequent attempts to cover-up those lies by punishing personally and vindictively a critic that was in a position to call those earlier lies into question. It is for these acts we want to see Libby and Rove punished. But those acts are not "crimes" in the legal sense. So, we want to get them for things we don't really care all that much about, but which nonetheless result in what we feel is well deserved punishment.

I don't deny a certain atavistic satisfaction seeing Libby indicted. Still, I must confess to being a bit embarrassed by that feeling, for there is a very great danger involved in saying, in effect, "Look, this is a very bad man who did very bad things, so we have to convict him of something, never mind what." It is hard to assure that such a genie, once let out of the bottle, will only be loosed on those who really deserve it.

Through The Looking Gas

I have some real problems with all of this."The financial results drew outrage from politicians and consumer advocates who see historically high U.S. gasoline prices as evidence of profiteering.

"This is a staggering profit and proof that we are being gouged by the oil industry," said Jamie Court of the Foundation for Taxpayer and Consumer Rights in Santa Monica.

Court said oil companies had refrained from building domestic refineries so that tight supplies would push up prices.

'Now Exxon needs to invest that money in making more gasoline,' he said. 'Neither Exxon nor the industry has opened a new refinery since 1976 because the companies know keeping refined supply low is a recipe for huge profits.'

Certainly, political pressure is building on the industry to increase its refining capacity, even from a GOP that this year championed an energy bill that included new subsidies for the oil and gas industry.

'These companies are turning in record profits 'they have a responsibility to expand,' Energy Secretary Samuel Bodman said Thursday before the Senate Energy Committee. Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist (R-Tenn.) called for an investigation of possible profiteering."

For one thing, the idea that it is the oil companies' fault that there have been no new refineries built in 30 years is laughable. The reason is the maze of regulation that any new refinery faces counpled with pervasive "nimby-ism". Everyone wants more gasoline, but they don't want to have anything to do with the processes required to make it, and they especially do not want these processes anywhere within sight. There is now one new refinery on the drawing board in Arizona. It has taken nearly 15 years and over $33 million to find an "acceptable" site and to obtain the necessary permits. It will take another 5 years and $3 billion to build it -- assuming it isn't killed by public opposition of ever changing governmental requirements in the mean time.

Problems like this have forced the industry to increase production at existing sites. Yet this process generated what has become known as the "USEPA Refinery Enforcement Initiative." The latest "victory" in this in initiative was aExxon to spend $590 million in unproductive capital and pay $18.4 million in penalties and penalty projects. EPA boasts that it has now subjected 77% of the industry to such "settlements."

I am not saying that there was no legal basis for such settlements. I am saying, though, as a lawyer who was deeply involved in some of these settlements, that the legal basis was far shakier than EPA will ever admit. Indeed, the thing that drove most of these companies to settle was that they had to get "peace" with EPA in order to pursue their plans for expanding production. The idea that the government is "shocked, just shocked" that we have a shortage of domestic refining capacity is utterly preposterous.

Another thing that bothers me is the idea that the refining industry controls the price of gasoline. That too is laughable. Three years ago, when gasoline was selling for $0.89/gallon and the refining industry was losing money hand over fist, no one complained. Now, when gasoline is pushing $3.00/gallon, everyone sees a conspiracy. Gasoline is a commodity just like sugar, flour, milk and coffee. Absent price-fixing or government price supports, the price of gas or any other commodity is dictated by supply and demand. There has been no allegation of price fixing in the industry (and given the intense level of competition and the number of competitors in the market, price fixing seems far-fetched) and there is certainly no price support by the government (except for the fact that a large chunk of the price of gas is taxes). Gas is high right now for one and only one reason: there is a lot more demand than there is supply.

The final point that bothers me is the notion that oil companies "have a responsibility to expand." If they have such a responsibility, it is not to the public but to their stockholders and it arises not because of past profits but because company managements believe that expansion will result in greater future profits. The oil companies are not public interest organizations. That is not to say that they should not act responsibly toward the public. But it is to say that they are not in the public service business and that they have no responsibility to expand except as dictated by their fiduciary duty to maximize shareholder value.

Gas prices are high because the demand for it has outstripped the supply. Supply is low because it has been constrained by governmental policy and public opposition to such an extent that the shut down of 10% of the domestic refining capacity due to hurricanes causes major dislocations in the market. Demand is high because we use so much. Everyone is in favor of conservation so long as it is someone else doing the conserving.

As Pogo said, "We have seen the enemy, and it us," not the oil companies.

Friday, October 28, 2005

Scooter Libbey Indicted

Indictment

Five counts: 1 on obstruction of Justice; 2 on false statements to the FBI; 2 of perjury before the grand jury. All for the same thing: statments that he had found out that Valerie Plame Wilson worked for the CIA from reporters, when he had actually found out from the State Department and other government officials (including Karl Rove?) and had himself already told Judy Miller.

Surpise surprise: There is no allegation that he broke the law in disclosing her identity.

I don't know. I guess we can't let stuff like this slide. But it somehow it just feels wrong to "get" people for stuff like this. What difference does it make where he heard it from, since it has seemed clear from the outset that there was not going to be any eveidence that he knew she was a covert operative. And, absent such knowledge, the outing was not an indictable offense.

Now, if being stupid were a crime, then Scooter really would be well-charged. How dumb can you possibly be? Do these people lie so much that they forget how to tell the truth, even when they know (or should know) that the lie will be uncovered?

Eating Crow To Krauthammer

In announcing the decision, Miers and Bush cited their concern with requests from members of the Senate Judiciary Committee for documents dealing with her work as White House counsel -- papers that the administration has withheld as privileged. Senators sought documents that might illuminate her legal views.From cronyism to hypocritical craveness. Bush has now abandoned the only thing I actually respected him for: determination. I can hardly wait to see who he appoints next.

"Protection of the prerogatives of the executive branch and continued pursuit of my nomination are in tension," Miers said in a withdrawal letter she hand-delivered to Bush yesterday. "I have decided that my confirmation should yield."

Wednesday, October 26, 2005

Monday, October 24, 2005

So, You Want A Real Crime?

[A]llies of the White House have quietly been circulating talking points in recent days among Republicans sympathetic to the administration, seeking to help them make the case that bringing charges like perjury mean the prosecutor does not have a strong case. . . . Other people sympathetic to Mr. Rove and Mr. Libby have said that indicting them would amount to criminalizing politics and that Mr. Fitzgerald did not understand how Washington works.As if on cue, the Wall Street Journal published an editorial today that appeared to be drawn directly from these talking points:

Some Republicans have also been reprising a theme that was often sounded by Democrats during the investigations into President Bill Clinton, that special prosecutors and independent counsels lack accountability and too often pursue cases until they find someone to charge.

Let's stipulate that the law is the law, and if Bush Administration officials lied to a grand jury in the clear and obvious way that Bill Clinton did, they should be prosecuted. If Mr. Fitzgerald has evidence of a malicious attempt to expose a CIA undercover agent, as defined by the relevant statute, the same applies. But the fact that the prosecutor has waited as long as he has--until the last days of his grand jury--suggests that he considers this a less than obvious case. A close call deserves to be a no call.The piece goes on to argue at length that (1) "outing" Valerie Plame was no big deal but was simply an "understandable" part of an effort by the administration to "fight back" against an accuser; and (2) violations of the 1917 Espionage Act (barring disclosure of classified information) are beyond Fitzgerald's original charge and so ubiquitous that, if regularly prosecuted, " half of Washington would be in jail." Kay Bailey Hutchison is reported to have made the same points on the Sunday talk show circuit:

All the more so because this entire probe began and has continued as a kind of proxy for the larger political war about the Iraq War.

Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison . . . compared the leak investigation with the case of Martha Stewart and her stock sale, "where they couldn't find a crime and they indict on something that she said about something that wasn't a crime."Sadly, perhaps, I find myself agreeing with them. As I wrote a few days ago:

Ms. Hutchison said she hoped "that if there is going to be an indictment that says something happened, that it is an indictment on a crime and not some perjury technicality where they couldn't indict on the crime and so they go to something just to show that their two years of investigation was not a waste of time and taxpayer dollars."

Well, if you want a real crime, Frank Rich has one for you.As much as I would like to see Rove and/or Libby go down, I do not want them to go down for a slip of the tongue, or a lapse in memory, or for a "crime" for which anyone in government might just as easily be convicted if subject to the same level of scrutiny. If they go down, I want it to be for something that the man in the street will look at and say, "if those allegations are true, that guy should be in jail.

In his Op-Ed piece Sunday (which you can't read, of course, unless you are a subscriber -- ugh!), Rich tells a story that, if true, would certainly warrant putting Rove and Libby and a whole bunch of other people in jail -- or worse:

[T]he leak investigation now reaching its climax in Washington continues to offer big clues [as to why we went into Iraq]. We don't yet know whether Lewis (Scooter) Libby or Karl Rove has committed a crime, but the more we learn about their desperate efforts to take down a bit player like Joseph Wilson, the more we learn about the real secret they wanted to protect: the "why" of the war.It seems far-fetched to suppose that Fitzgerald's investigation will come out with something approacing proof of Rich's theory. But if they do, then jail is much too good for these people.

* * * *

In Mr. Rove's case, let's go back to January 2002. By then the post-9/11 war in Afghanistan had succeeded in its mission to overthrow the Taliban and had done so with minimal American casualties. In a triumphalist speech to the Republican National Committee, Mr. Rove for the first time openly advanced the idea that the war on terror was the path to victory for that November's midterm elections. Candidates "can go to the country on this issue," he said, because voters "trust the Republican Party to do a better job of protecting and strengthening America's military might and thereby protecting America." It was an early taste of the rhetoric that would be used habitually to smear any war critics as unpatriotic.

But there were unspoken impediments to Mr. Rove's plan that he certainly knew about: Afghanistan was slipping off the radar screen of American voters, and the president's most grandiose objective, to capture Osama bin Laden "dead or alive," had not been achieved. How do you run on a war if the war looks as if it's shifting into neutral and the No. 1 evildoer has escaped?

* * * *

[This was compounded by] a rapid barrage of unhelpful news for a political campaign founded on supposed Republican superiority in protecting America: the first report (in The Washington Post) that the Bush administration had lost Bin Laden's trail in Tora Bora in December 2001 by not committing ground troops to hunt him down; the first indications that intelligence about Bin Laden's desire to hijack airplanes barely clouded President Bush's August 2001 Crawford vacation; the public accusations by an F.B.I. whistle-blower, Coleen Rowley, that higher-ups had repeatedly shackled Minneapolis agents investigating the so-called 20th hijacker, Zacarias Moussaoui, in the days before 9/11.

These revelations took their toll. By Memorial Day 2002, a USA Today poll found that just 4 out of 10 Americans believed that the United States was winning the war on terror, a steep drop from the roughly two-thirds holding that conviction in January. Mr. Rove could see that an untelevised and largely underground war against terrorists might not nail election victories without a jolt of shock and awe. It was a propitious moment to wag the dog.

Enter Scooter, stage right. As James Mann details in his definitive group biography of the Bush war cabinet, "Rise of the Vulcans," Mr. Libby had been joined at the hip with Dick Cheney and Paul Wolfowitz since their service in the Defense Department of the Bush 41 administration, where they conceived the neoconservative manifesto for the buildup and exercise of unilateral American military power after the cold war. Well before Bush 43 took office, they had become fixated on Iraq, though for reasons having much to do with their ideas about realigning the states in the Middle East and little or nothing to do with the stateless terrorism of Al Qaeda. Mr. Bush had specifically disdained such interventionism when running against Al Gore, but he embraced the cause once in office. While others might have had cavils - American military commanders testified before Congress about their already overtaxed troops and equipment in March 2002 - the path was clear for a war in Iraq to serve as the political Viagra Mr. Rove needed for the election year.

But here, too, was an impediment: there had to be that "why" for the invasion, the very why that today can seem so elusive that Mr. Packer calls Iraq "the 'Rashomon' of wars." Abstract (and highly debatable) neocon notions of marching to Baghdad to make the Middle East safe for democracy (and more secure for Israel and uninterrupted oil production) would never fly with American voters as a trigger for war or convince them that such a war was relevant to the fight against those who attacked us on 9/11. And though Americans knew Saddam was a despot and mass murderer, that in itself was also insufficient to ignite a popular groundswell for regime change. Polls in the summer of 2002 showed steadily declining support among Americans for going to war in Iraq, especially if we were to go it alone.

For Mr. Rove and Mr. Bush to get what they wanted most, slam-dunk midterm election victories, and for Mr. Libby and Mr. Cheney to get what they wanted most, a war in Iraq for reasons predating 9/11, their real whys for going to war had to be replaced by fictional, more salable ones. We wouldn't be invading Iraq to further Rovian domestic politics or neocon ideology; we'd be doing so instead because there was a direct connection between Saddam and Al Qaeda and because Saddam was on the verge of attacking America with nuclear weapons. The facts and intelligence had to be fixed to create these whys; any contradictory evidence had to be dismissed or suppressed.

Mr. Libby and Mr. Cheney were in the boiler room of the disinformation factory. The vice president's repetitive hyping of Saddam's nuclear ambitions in the summer and fall of 2002 as well as his persistence in advertising bogus Saddam-Qaeda ties were fed by the rogue intelligence operation set up in his own office. As we know from many journalistic accounts, Mr. Cheney and Mr. Libby built their "case" by often making an end run around the C.I.A., State Department intelligence and the Defense Intelligence Agency. Their ally in cherry-picking intelligence was a similar cadre of neocon zealots led by Douglas Feith at the Pentagon.

THIS is what Col. Lawrence Wilkerson, then-Secretary of State Colin Powell's wartime chief of staff, was talking about last week when he publicly chastised the "Cheney-Rumsfeld cabal" for sowing potential disaster in Iraq, North Korea and Iran. It's this cabal that in 2002 pushed for much of the bogus W.M.D. evidence that ended up in Mr. Powell's now infamous February 2003 presentation to the U.N. It's this cabal whose propaganda was sold by the war's unannounced marketing arm, the White House Iraq Group, or WHIG, in which both Mr. Libby and Mr. Rove served in the second half of 2002. One of WHIG's goals, successfully realized, was to turn up the heat on Congress so it would rush to pass a resolution authorizing war in the politically advantageous month just before the midterm election.

Joseph Wilson wasn't a player in these exalted circles; he was a footnote who began to speak out loudly only after Saddam had been toppled and the mission in Iraq had been "accomplished." He challenged just one element of the W.M.D. "evidence," the uranium that Saddam's government had supposedly been seeking in Africa to fuel its ominous mushroom clouds.

But based on what we know about Mr. Libby's and Mr. Rove's hysterical over-response to Mr. Wilson's accusation, he scared them silly. He did so because they had something to hide. Should Mr. Libby and Mr. Rove have lied to investigators or a grand jury in their panic, Mr. Fitzgerald will bring charges. But that crime would seem a misdemeanor next to the fables that they and their bosses fed the nation and the world as the whys for invading Iraq.

Here We Go Again

That Oct. 16 statement reflected some of the pitfalls associated with releasing such statistics. The number was immediately challenged by witnesses, who said many of those killed were not insurgents but civilians, including women and children.

[Also,] several uniformed military and civilian defense officials . . . questioned the effectiveness of citing such figures in conflicts where the enemy has shown itself capable of rapidly replacing dead fighters and where commanders acknowledge great uncertainty about the total size of the enemy force.

Sunday, October 23, 2005

More On Miers (Sigh)

Arlen, after trashing Miers' questionaire response, now seems to have little patience for those who would pillory her even before she has a real chance to defend herself. He seems to think people ought to let her speak before they condemn her. What a concept!!

Except that, she's SUCH a fawning, sychophantic, toady!

I honestly don't know how anyone could vote for her to be on the Supreme Court. Those that do will fall into one of two camps: those who believe in Bush and those who believe "it could be worse."

I find myself leaning toward the "it could be worse" camp. At least she's not Bork.

But then I get mad. We shouldn't have to settle for someone whose only redeeming virtue is that she's not a troglodyte.

This President sucks.

That's my considered opinion.

Saturday, October 22, 2005

Angst At The Times

I don't know. Maybe I am just too attached to this paper. But I find it hard to imagine any other media outlet in the country having the courage to to this sort of thing.Colleagues,

As you can imagine, I’ve done a lot of thinking -- and a lot of listening -- on the subject of what I should have done differently in handling our reporter’s entanglement in the White House leak investigation. Jill and John and I have talked a great deal among ourselves and with many of you, and while this is a discussion that will continue, we thought it would be worth taking a first cut at the lessons we have learned.

Aside from a number of occasions when I wish I had chosen my words more carefully, we’ve come up with a few points at which we wish we had made different decisions. These are instances, when viewed with the clarity of hindsight, where the mistakes carry lessons beyond the peculiar circumstances of this case.

I wish we had dealt with the controversy over our coverage of WMD as soon as I became executive editor. At the time, we thought we had compelling reasons for kicking the issue down the road. The paper had just been through a major trauma, the Jayson Blair episode, and needed to regain its equilibrium. It felt somehow unsavory to begin a tenure by attacking our predecessors. I was trying to get my arms around a huge new job, appoint my team, get the paper fully back to normal, and I feared the WMD issue could become a crippling distraction.

So it was a year before we got around to really dealing with the controversy. At that point, we published a long editors’ note acknowledging the prewar journalistic lapses, and -- to my mind, at least as important - - we intensified aggressive reporting aimed at exposing the way bad or manipulated intelligence had fed the drive to war. (I’m thinking of our excellent investigation of those infamous aluminum tubes, the report on how the Iraqi National Congress recruited exiles to promote Saddam’s WMD threat, our close look at the military’s war-planning intelligence, and the dissection, one year later, of Colin Powell’s U.N. case for the war, among other examples. The fact is sometimes overlooked that a lot of the best reporting on how this intel fiasco came about appeared in the NYT.)

By waiting a year to own up to our mistakes, we allowed the anger inside and outside the paper to fester. Worse, we fear, we fostered an impression that The Times put a higher premium on protecting its reporters than on coming clean with its readers. If we had lanced the WMD boil earlier, we might have damped any suspicion that THIS time, the paper was putting the defense of a reporter above the duty to its readers.

I wish that when I learned Judy Miller had been subpoenaed as a witness in the leak investigation, I had sat her down for a thorough debriefing, and followed up with some reporting of my own. It is a natural and proper instinct to defend reporters when the government seeks to interfere in our work. And under other circumstances it might have been fine to entrust the details -- the substance of the confidential interviews, the notes -- to lawyers who would be handling the case. But in this case I missed what should have been significant alarm bells. Until Fitzgerald came after her, I didn’t know that Judy had been one of the reporters on the receiving end of the anti-Wilson whisper campaign. I should have wondered why I was learning this from the special counsel, a year after the fact. (In November of 2003 Phil Taubman tried to ascertain whether any of our correspondents had been offered similar leaks. As we reported last Sunday, Judy seems to have misled Phil Taubman about the extent of her involvement.) This alone should have been enough to make me probe deeper.

In the end, I’m pretty sure I would have concluded that we had to fight this case in court. For one thing, we were facing an insidious new menace in these blanket waivers, ostensibly voluntary, that Administration officials had been compelled to sign. But if I had known the details of Judy’s entanglement with Libby, I’d have been more careful in how the paper articulated its defense, and perhaps more willing than I had been to support efforts aimed at exploring compromises.

Dick Stevenson has expressed the larger lesson here in an e-mail that strikes me as just right: “I think there is, or should be, a contract between the paper and its reporters. The contract holds that the paper will go to the mat to back them up institutionally -- but only to the degree that the reporter has lived up to his or her end of the bargain, specifically to have conducted him or herself in a way consistent with our legal, ethical and journalistic standards, to have been open and candid with the paper about sources, mistakes, conflicts and the like, and generally to deserve having the reputations of all of us put behind him or her. In that way, everybody knows going into a battle exactly what the situation is, what we’re fighting for, the degree to which the facts might counsel compromise or not, and the degree to which our collective credibility should be put on the line.”

I’ve heard similar sentiments from a number of reporters in the aftermath of this case.

There is another important issue surfaced by this case: how we deal with the inherent conflict of writing about ourselves. This paper (and, indeed, this business) has had way too much experience of that over the past few years. Almost everyone we’ve heard from on the staff appreciates that once we had agreed as an institution to defend Judy’s source, it would have been wrong to expose her source in the paper. Even if our reporters had learned that information through their own enterprise, our publication of it would have been seen by many readers as authoritative -- as outing Judy’s source in a backhanded way. Yet it is excruciating to withhold information of value to our readers, especially when rival publications are unconstrained. I don’t yet see a clear-cut answer to this dilemma, but we’ve received some thoughtful suggestions from the staff, and it’s one of the problems that we’ll be wrestling with in the coming weeks.

Best, Bill

Being the best of the best is hard.

Maureen Dowd on Judy Miller: Woman of Mass Destruction

Since the Times will no longer let you read its Op-Ed columnists without subscribing at $50/year, I will have give you a taste:

That last sentence is vintage Dowd. But I share with her the sense that it's probably time for Judy Miller to "retire" and go write her book.I've always liked Judy Miller. . . . The traits she has that drive many reporters at The Times crazy - her tropism toward powerful men, her frantic intensity and her peculiar mixture of hard work and hauteur - have never bothered me. I enjoy operatic types. * * * *

She never knew when to quit. That was her talent and her flaw. Sorely in need of a tight editorial leash, she was kept on no leash at all, and that has hurt this paper and its trust with readers. She more than earned her sobriquet "Miss Run Amok."

Judy's stories about W.M.D. fit too perfectly with the White House's case for war. She was close to Ahmad Chalabi, the con man who was conning the neocons to knock out Saddam so he could get his hands on Iraq, and I worried that she was playing a leading role in the dangerous echo chamber that Senator Bob Graham, now retired, dubbed "incestuous amplification." Using Iraqi defectors and exiles, Mr. Chalabi planted bogus stories with Judy and other credulous journalists.

* * * *

Judy admitted in the story that she "got it totally wrong" about W.M.D. "If your sources are wrong," she said, "you are wrong." But investigative reporting is not stenography.

The Times's story [about her role in the Plame investigation] and Judy's own first-person account had the unfortunate effect of raising more questions. As Bill [Keller, the Times Editor] said yesterday in an e-mail note to the staff, Judy seemed to have "misled" the Washington bureau chief, Phil Taubman, about the extent of her involvement in the Valerie Plame leak case.

She casually revealed that she had agreed to identify her source, Scooter Libby, Dick Cheney's chief of staff, as a "former Hill staffer" because he had once worked on Capitol Hill. The implication was that this bit of deception was a common practice for reporters. It isn't.

She said that she had wanted to write about the Wilson-Plame matter, but that her editor would not allow it. But Managing Editor Jill Abramson, then the Washington bureau chief, denied this, saying that Judy had never broached the subject with her.

It also doesn't seem credible that Judy wouldn't remember a Marvel comics name like "Valerie Flame." Nor does it seem credible that she doesn't know how the name got into her notebook and that, as she wrote, she "did not believe the name came from Mr. Libby."

An Associated Press story yesterday reported that Judy had coughed up the details of an earlier meeting with Mr. Libby only after prosecutors confronted her with a visitor log showing that she had met with him on June 23, 2003. This cagey confusion is what makes people wonder whether her stint in the Alexandria jail was in part a career rehabilitation project.

Judy refused to answer a lot of questions put to her by Times reporters, or show the notes that she shared with the grand jury. I admire Arthur Sulzberger Jr. and Bill Keller for aggressively backing reporters in the cross hairs of a prosecutor. But before turning Judy's case into a First Amendment battle, they should have nailed her to a chair and extracted the entire story of her escapade.

Judy told The Times that she plans to write a book and intends to return to the newsroom, hoping to cover "the same thing I've always covered - threats to our country." If that were to happen, the institution most in danger would be the newspaper in your hands.

Friday, October 21, 2005

A Rose By Any Other Name

DHMO.org

Get it? Next time you see another "alert" on toxic chemicals, remember this. And be skeptical.

It's the Cover-up

Told you so. Valerie Plame will be all but forgotten.As he weighs whether to bring criminal charges in the C.I.A. leak case, Patrick J. Fitzgerald, the special counsel, is focusing on whether Karl Rove, the senior White House adviser, and I. Lewis Libby Jr., chief of staff for Vice President Dick Cheney, sought to conceal their actions and mislead prosecutors, lawyers involved in the case said Thursday.

Among the charges that Mr. Fitzgerald is considering are perjury, obstruction of justice and false statement - counts that suggest the prosecutor may believe the evidence presented in a 22-month grand jury inquiry shows that the two White House aides sought to cover up their actions, the lawyers said.

Grasping at Straws

Miers withdraws out of respect for both the Senate and the executive's prerogatives, the Senate expresses appreciation for this gracious acknowledgment of its needs and responsibilities, and the White House accepts her decision with the deepest regret and with gratitude for Miers's putting preservation of executive prerogative above personal ambition.Lame. And desperate. And totally bogus.

I have no idea what will happen with Miers. But I think we can all be pretty confident that the Senate will not (ever)"express appreciation for [a nominee's] gracious acknowledgment of its needs and responsibilities."

Thursday, October 20, 2005

Sympathy For Condi

In three and a half hours of hearings at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Ms. Rice was both conciliatory and combative, rebutting the gloomy assessments from senators of both parties but at the end offering a weary concession to Senator Barack Obama, Democrat of Illinois.It is hard (espically for those like billy bob who might actually have to go over there and fight) to separate the justness of our being there from the necessity for doing what we are now that the die has been cast. But that is a separation that needs to be made.

"I understand that, yes, it might not work," Ms. Rice told Mr. Obama, referring to American plans to raise the effectiveness of Iraqi forces and heal Iraq's fractious society. "But every day we have to get up and work at our hardest to make it work."

As Rice recognizes, we may fail in bringing stability to Iraq. But I just do not see how we can give up on the effort, at least yet.

It is good to hear a note of humility, of a recognitions that there are limits to what we can do. But Condi fell well short of what really needs to be said. Here's what I would have liked to hear from the Administration:

Senator, let me start with an apology. We should never have gone into Iraq. I won't go into all of the ratioanles we had for the decision. There were many: some sound; some unsound; some entirely specious; some bordering on the delusional. I will leave it to history to evaluate all of that. But one thing we can say with certainty is that we made a very bad decision.Had theAdministration said something like this two years ago or even a year ago, the whole attitude of the country toward the war would likely be very different. As it stands now, though, it may be too late. We have reached a tipping point. The public is tired and frustrated, the President is crippled, support for the war is virtually nil, active opposition is on the rise, and even Republicans are beginning to demand schedules for bringing the troops home regardless of the results. We are on the verge of cutting and running. And, if we do, I shudder to think of the potential consequences.But the decision was made and, much as we might like to, we cannot now unmake it. We are there. The country is in chaos. And it is vitally important for America, the West, the Arab world and Iraq that stability be restored. I understand that, yes, it might not work, that we may fail. But every day we have to get up and work at our hardest to make it work.

Wednesday, October 19, 2005

Ditch Roe v Wade?

But be that as it may, though, I can't say I would be sorry to see the decision overturned. It is a black hole sitting at the center of our domestic policy, swallowing or at least badly warping everything around it, and I am coming to the conclusion that America might well be better off if it went away.

The debate around the Miers nomination is just the most recent example of this black hole effect. In his Op-Ed piece today, Tom Friedman imagines how that debate might look to an Iraqi:

"The lead Iraqi delegate, Muhammad Mithaqi, a noted secular Sunni judge who had recently survived an assassination attempt by Islamist radicals, said that he was stunned when he heard President Bush telling Republicans that one reason they should support Harriet Miers for the U.S. Supreme Court was because of 'her religion.' She is described as a devout evangelical Christian.Robert Bork makes essentially the same point, albeit for very different reasons, in an Op-Ed piece in today's WSJ:

Mithaqi said that after two years of being lectured to by U.S. diplomats in Baghdad about the need to separate 'mosque from state' in the new Iraq, he was also floored to read that the former Whitewater prosecutor Kenneth Starr, now a law school dean, said on the radio show of the conservative James Dobson that Miers deserved support because she was 'a very, very strong Christian [who] should be a source of great comfort and assistance to people in the households of faith around the country.'

'Now let me get this straight,' Judge Mithaqi said. 'You are lecturing us about keeping religion out of politics, and then your own president and conservative legal scholars go and tell your public to endorse Miers as a Supreme Court justice because she is an evangelical Christian.

The administration's defense of the nomination is pathetic: Ms. Miers . . . is, as an evangelical Christian, deeply religious. That last, along with her contributions to pro-life causes, is designed to suggest that she does not like Roe v. Wade, though it certainly does not necessarily mean that she would vote to overturn that constitutional travesty.

There is a great deal more to constitutional law than hostility to Roe.

Yes indeed there is. But that is like saying there is more to life than money. Sure, there's more to constitutional law than Roe, but in terms of qualifications to be a Supreme Court Justice, Roe if far ahead of whatever is in second place.

Even more distressing to me, Roe is the great engine of the Christian Right. Where would people like James Dobson and Tony Perkins be without Roe? I seriously doubt if we would ever have heard of them. Now that this monster exists, getting rid of it may take more than elimination of Roe. There are new dragons they want to slay: gay marriage, homosexuality generally, assisted suicide, stem cell research, etc. But none of those has the "legs" that abortion has. And, if the Right ever were successful in getting rid of Roe, I suspect it would generate a significant backlash from the "silent majority" of Americans who, while ambivalent about abortion, nonetheless believe they should not be illegal and who are even less comfortable with the rest of the Christian Right's agenda. In short, my guess is that, deprived of Roe, the cohesion and political power of the Christian Right would begin to wane.

And, what would be the downside? Overturning Roe does not make abortion illegal. It simply leaves the States free to legislate in the area. Abortion would likely remain legal in most of the "Blue States," and even in the "Red States" it will be interesting to see State legislators grapple with the issue once they have to quit sloganeering and take political and moral responsibility for the decision themselves.

Some states will doubtless move quickly to enact abortion bans, and in those states there is likely to be an upsurge in both back-alley abortion deaths and unwanted, uncared-for children. That is sad, certainly. But the battle over abortion is a war and the fact that there are casualties tends to bring the question "is it worth it" into much sharper focus.

And, in the meantime, the Country can get back to being able to think about something other than abortion. That would be a very good thing.

Tuesday, October 18, 2005

Rove and Libby Indictment Probability

This sort of stuff is fun, but Tierney has a different point: The odds are this high because everyone realizes that a prosecutor armed with virtually unlimited time and resources will always find a crime. In many cases, it will not be the crime that originally launched the investigation, but something else, frequently a crime that is committed as a part of the investigation itself (e.g. lying to a federal official, obstruction of justice, perjury, etc.) or a common practices that can be made out to be a technical violation of some other statute (e.g. disclosure of classified information).

Tierney thinks there is something wrong with this, and so do I. But Tierney's solution is to quit appointing special prosecutors:

The lesson for the public would be: stop appointing special prosecutors. The job can turn a reasonable lawyer into an inquisitor with the zeal of Captain Ahab - even more zeal, actually, because he'll keep hunting even after he learns there's no whale. He'll settle for anything else he can scare up.But that is not the answer. Absent a special prosecutor, we would have to rely on the Administration to investigate itself. Can you imagine relying on the Nixon Administration investigating Watergate, for instance? Vowing never to appoint a special prosecutor is, effectively, vowing give up on investigating wrongdoing by high federal officials altogether.

But Tierney's general point is well taken. Sooner or later, if the full investigatory power of the government is directed at any individual, a "crime" will be uncovered. For ordinary citizens, the prosecutor will frequently determine that the crime is so minor or technical as to not warrant prosecution. But when the person in the cross hairs is a public figure, especially one as controversial as Karl Rove or Scooter Libby, "ignoring" evidence of a crime becomes very difficult to do, even if the Prosecutor is not someone trying to make a name for himself -- which is itself a rare thing.

Part of the answer, of course, is to not appoint so many special prosecutors. There ought to be some evidence that a "real" crime was actually committed before moving to a special prosecutor. I don't think "outing" Valerie Plame rises to that level.

In the end, though, we have to rely on the ability and willingness of the Prosecutor to exercise some judgment as to when to indict and when not to. One of Tierny's sources believes that Fitzgerald, at least, may have and be willing to exercise such judgment:

Maybe we're all misreading Fitzgerald's diligence. One former federal prosecutor now in private practice told me that Fitzgerald might just be protecting himself, investigating every conceivable offense before concluding that whatever corners were cut, there's no reason to indict.As much as I would like to see Rove and/or Libby go down, I do not want them to go down for a slip of the tongue, or a lapse in memory, or for a "crime" for which anyone in government might just as easily be convicted if subject to the same level of scrutiny. If they go down, I want it to be for something that the man in the street will look at and say, "if those allegations are true, that guy should be in jail."

"Fitzgerald is a lot more solid and experienced than Ken Starr," the former prosecutor told me. "He knows that if you investigate any case long enough, you'll end up with a bunch of witnesses you could accuse of perjury and obstruction of justice. But that doesn't mean you indict them. Real crime is what happens before the investigation starts."

Wilma Update

New Orleans mayor Ray Nagan is taking no chances, though: New Orleans May Face Another Evacuation

The "Roberts Court's" First Abortion Decision

See this: High Court Allows Inmate's Abortion

It's hard to know what (if anything) to make of this, but it is interesting.

Body Counts

Well, imagine that!

I didn't trust body counts 35 years ago from the Johnson Administration and I have no greater faith in them now. The counts themselves may well be accurate, but the definition of "insurgent" is "anyone we kill." Especially when one is doing the killing from the air in crowded metropolitan areas, it defies reason to suppose that all of the bodies are those of enemies.

There is a humanitarian issue here, of course, but the real problem with branding as insurgents anyone killed in a riad or bombing is that it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Every time you kill or maim and inocent bystander, you create potential insurgents out of an entire extended family.

As long as we are there, we have to fight the insugency, and as long as we fight the insurgency, we will inevitably kill or injure people who are not a part of it. But, it would be nice if the US started to admit publicly that there is appreciable collateral damage every time the stage one of these operations; to take some time and effort to determine who was who; and to apologize, try to console and/or compensate the unintended victims.

Monday, October 17, 2005

In The Age Of Global Competition, Whither American Labor?

America's working middle class has been eroding for a generation, and it may be about to wash away completely. Something must be done.Given Krugman's agenda, the "wash away" metaphor is effective, evoking both the destruction wreaked by the Katrina flooding and the conviction that the government should have done something to prevent or at least mitigate that destruction. But it is a tad melodramatic don't you think? American workers are being squeezed, there's no doubt about that. But washed away? For all of their problems, American workers remain the best paid in the world, and I doubt seriously if any of them are or will soon look longingly at the wages and working conditions "enjoyed" by the Chinese and Indian workers with whom they are competing.

Still, the phenomenon Krugman describes is real and its causes and implications are well worth thinking about:

There was a time when the American economy offered lots of good jobs - jobs that didn't make workers rich but did give them middle-class incomes. The best of these good jobs were at America's great manufacturing companies, especially in the auto industry.Labor is a commodity, and, like any commodity, the "value" of labor (i.e. the price a labor consumer is willing or able to pay for that labor) declines as the supply increases and/or the demand decreases. This is not to say all labor is the same. Far from it. Just as sugar is not a substitute for diamonds, so too an autoworker is not a substitute for a brain surgeon. And, like diamonds, brain surgery is more "valuable" than auto repair precisely because brain surgeons are rarer than auto mechanics. (This difference is due only in part to the fact that the abilities required for brain surgery are rarer and the knowledge more difficult to obtain than are the abilities and knowledge necessary for auto repair. The supply of brain surgeons is also constrained by shortages of medical schools, licensing requirements, and immigration restrictions while demand for brain surgery is kept high by heavy subsidization in the form of insurance. But that is a subject for another time). Even within a given labor sector there are differences. A worker who can make 10 widgets per hour with $10 of capital, is worth considerably more than a worker who can make 1 widget per hour with $5 of capital. But the point is still obvious: Whatever the goods or services, if worker A can produce output comparable to worker B at a lower total cost, then worker A's wages will tend to rise and worker B's will tend to fall, unless there is some impediment that prevents worker A from competing with worker B.

But it has been a generation since most American workers could count on sharing in the nation's economic growth. America is a much richer country than it was 30 years ago, but since the early 1970s the hourly wage of the typical worker has barely kept up with inflation.

The contrast between rising national wealth and stagnant wages has become even more extreme lately. In 2004, which was touted both by the Bush administration and by Wall Street as a year in which the economy boomed, the median real income of full-time, year-round male workers fell more than 2 percent.

Now the last vestiges of the era of plentiful good jobs are rapidly disappearing. Almost everywhere you look, corporations are squeezing wages and benefits, saying that they have no choice in the face of global competition. And with the Delphi bankruptcy, the big squeeze has reached the auto industry itself.

During the period of American history to which Krugman devotes his nostalgia, the supply of labor available to American manufacturers was constrained by geographical factors and the demand was enhanced by relatively low productivity. This has now changed. Advances in technology, communication and transportation have vastly increased the available supply of labor at the same time that increases in productivity have reduced demand for it. It doesn't take a Nobel Prize in economics to realize that these factors -- especially in combination -- are going to put a squeeze on the best paid of the workers in the labor pool -- Americans -- while giving a boost to the wages of comparable laborers who are currently paid far less -- the Chinese and Indians for example. The net effect is that, absent political interference, global wage inequalities will tend to diminish. That is bad news for American workers, but it is very good news for Chinese workers.

If this equalization were occurring between sections of the United States itself, we would not be all that concerned. In fact, exactly that sort of a realignment did occur in the United States as manufacturing jobs steadily left the Rust Belt for the Sun Belt beginning in the 60s. But when the equalization starts crossing international boundaries, the whole issue gets bound up with nationalism. The question Krugman is actually asking is how do we maintain the artificially high wages of American workers while keeping the wages of comparable Chinese and Indian workers artificially low. Nationalism prevents him from even thinking about whether that is a worthwhile goal.

Krugman rightly fears the political implications of this trend:

What if neither education nor health care reform is enough to end the wage squeeze? That's the possibility that makes free-trade liberals like me very nervous, because at that point protectionism enters the picture. When corporate executives say that they have to cut wages to meet foreign competition, workers have every right to ask why we don't cut the foreign competition instead.I don't know whether workers have the "right" to ask for protection, but I certainly do agree that they will ask for it. Indeed, they are asking for -- and in some cases getting -- it already.

Protectionism is a very bad idea. But even the most compelling economic arguments are not going to be enough to meet the political demand to protect American wages. So, in the end, Krugman's question is a valid one: what do we do to prevent a continuing squeeze on wages from triggering a political reaction that ends in protectionism or worse?

I don't know exactly, but I do know this much: Any solution that will work has to fit the economic realities rather than fight them. The economic reality this: traditional mass production will no longer support the relative wage levels it did a generation ago. There is simply too much competition, and the global leveling of wages that results from this competition is going to inexorably and unavoidably reduce the difference in wages between American and foreign mass production workers. In the end, I think the wages of foreign workers are likely to rise faster than the wages of American workers will fall, since manufacturers in India and China will inevitably be faced with the same types of demands for higher wages and benefits and for collective bargaining that American manufacturers faced a century ago. But, the prospect for maintaining the present gap between American and foreign manufacturing wages is virtually nil. There is nothing that government can do to change that fact, and asking it to try is like asking King Canute to stop the tide from coming in.

If high American wages are to be maintained, the only real option is for Americans to find different things to do; things for which the global labor pool is much smaller. The obvious candidate is the so-called "knowledge" or "information" economy. Krugman is skeptical about this as an option:

During the 1990s optimists argued that better education and worker training could restore the economy's ability to create good jobs. Mr. Miller of Delphi picked up that argument as part of his public relations campaign for wage cuts: "The world pays knowledge workers far more than it pays manual, industrial workers," he said. "And that's what's sweeping over here."But his skepticism is based on three mistakes. The first is to write off the knowledge economy simply because that economy is not immune to layoffs. Yes, the bubble of late 90s resulted in a rate of computer and internet-related job creation that could not be sustained. But, does anyone doubt that the computer/internet industry is a huge source of job growth in America or that these kinds of jobs pay more than mass production jobs?

But that's a very 1999 sort of answer. During the technology bubble, it was easy to believe that "knowledge workers" were guaranteed good jobs. But when the bubble burst, they turned out to be as vulnerable to downsizing and layoffs as assembly-line workers. And many of the high-paid jobs that vanished when the technology bubble burst have never come back, partly because they have been outsourced to India and other rising economies.

The second mistake is that Krugman seems to think that the "new" jobs should continue to provide Americans with higher wages than the rest of the world for a period of time comparable to what manufacturing did. This is not going to happen. Inevitably, American workers are going to face global competition even in the knowledge economy, and that competition is going to put pressure on high American wages in those areas. Further, this process is going to happen at an ever accelerating rate. Thus, if American workers are going to continue to be the best paid in the world, they are going to need to do re-invent themselves over and over again.

Finally, Krugman makes the mistake of equating the "knowledge economy" with the computer/dot com economy. Computers, the internet and dot coms are important, but they are only a very, very small piece of the knowledge economy. It is more realistic to equate the knowledge economy with the service economy.

When we talk of "service" jobs, we tend to think of people flipping hamburgers or greeting customers at Wal-Mart. But the service economy also includes doctors, lawyers, accountants, consultants, counselors, educators, carpenters, plumbers, truck drivers, stock brokers, financial consultants, financial analysts, commodity traders, bankers, scientists, engineers, designers, decorators, photographers, journalists, pundits, entertainers, etc., etc., etc. These are all jobs that will pay American workers as well or better than the manufacturing jobs Krugman pines for. Also, many of these jobs are far better insulated from competition by foreign workers than are manufacturing jobs, since most require or are at least significantly enhanced by face-to-face interactions with the consumer. It is to these types of jobs that Americans need to move to if we are to maintain a standard of living higher than any other country on earth.

What role does government have in this? Not much, frankly. Indeed the great danger is that government will get in the way. The protectionism that Krugman fears is the most obvious counter-productive response, since, at best, protectionism will only serve to delude people into thinking that America of the 1950s can be preserved. But, there is a useful role for government in three areas: education, education and education.

I am not talking solely about the type of education you get in school. A big part of what is needed to make doctors out of steelworkers or carpenters out of coal miners is to convince the people who might otherwise become steel workers or coal miners that the future lies elsewhere and that they have to ability to go to that other place. Also, we need to educate parents about education; not just the value of it but their role in assuring that their children get it. Efforts to force schools to raise the academic standards and to be accountable for failures to do so are probably necessary, but the real need is to convince parents that the key to their children's education lies not with the schools but with them.

Finally, of course, we need broader access to higher education. Without that, urging the importance of education on parents and children becomes a cruel joke. We will have created a demand that cannot be met. If we are to meet the challenge that global competition poses to those who would otherwise end up in the mass production economy, we have to provide those people with the actual opportunity pursue the alternatives. I don't have an easy answer to how this should be done, but I do think I know what needs to be done. The goal needs to be to assure that every child who wants to can get the education he or she needs to move into the knowledge economy.

In the long run, I do not think the current gap between American and foreign wages is sustainable. It is just too big. Also, one can well ask whether it is important to maintain that gap. Arguably, we should not object if other countries reach our standard of living so long as that standard of living is adequate (whatever that means). But, I do think that trying to maintain the gap is worthwhile so long as the means we use are designed to increase American wages rather than trying to prevent increases in foreign wages. Regardless of whether such efforts are successful in maintaining American wage leadership, the effort to achieve that goal will benefit us all.

The Slimiest Man On Earth? Probably Not, Unfortuantely

It is an amazing story of unprincipled, no-holds-barred "lobbying." One could hope, I guess, that this type of stuff is unusual, but I suppose that would be naive.

The Toledo Riots

YOUNG black people, let me be blunt: The march by hate groups in North Toledo today is aimed at you. Don't give them the time of day. Please.Sadly, they didn't listen.

If the hate groups can upset you enough to cause you to react and get arrested, or cause you to show an outburst of violence, then they will have accomplished their goal.

Don't give them that satisfaction, no matter how upset they might make you, and believe me, their words can make a minority pretty upset. You are not what they say you are, so stay home, do something else, or go to some worthwhile community function instead.

I really do not know what to say about the riots. One would dearly love to blame the Nazis, as utterly dispicable as they are. But they didn't do it. It was the people themselves. One would like to blame economic conditions or frustrations generated by racism. But that is nonsense as well. The truth is that the riots were pure hooliganism: destruction of property for the sheer fun of it. The Nazis simply provided a convenient excuse.

Sunday, October 16, 2005

The Times: Reporting On Itself -- Again

It's a good piece -- as far as it goes. Yet even here, the Times seems peculiarly bent on self-justification. It's almost like Bush saying, in response to the Katrina mess "If there were any failings in the federal response, I take full responsibility." They can't quite admit what seems reasonably obvious to most people: They were duped into taking a stand on behalf of a self-serving reporter whose primary mission was not to protect a source but to make herslf a star -- and who had not the guts to play the game out to the end.

The Times does deserve credit for at least examining itself. One could wish that they didn't get so much practice at it, though.

Friday, October 14, 2005

Off The Beaten Track

Astronomers Surprised: Stars Born Near Black Hole

Black holes are sooooo cool.

Irresistible Force Meets Immovable Object

I know, it's old news. But the interesting thing is it has no sign of abating. In fact, every day that goes by, it gets worse.

Can anyone imagine Meirs being confirmed? Bush simply does not have (any more) the political muscle to enforce party unity, and in the absence of that it is hard to see how Miers can get 50 votes in the Senate. In fact, this one could go down in Committee. Yet, can anyone imagine Bush withdrawing the nomination? If he does, even he has to know that he might as well go back to Crawford for the next three years.

DeLay, Frist, Rove. And Meirs.

We are watching a slow motion trainwreck.

4 1/2 HOURS??

Rove testified for 4 1/2 hourse before the Fitzgerald gand jury. And this is the fourth time he has testified. It's beginning to look more and more like Rove might actually be a target. Indeed, prosecutors apparently told Rove, before he testified, that they could not guarantee he would not be indicted.

My guess is that the disclosure of Valerie Plame's identity is now actually the least of Karl's worries. His real worry now is going to be obstruction of justice and even perjury. They don't have someone back four times to a grand jury and on the last time grill him for 4 1/2 hours, just to find out what he knew. They have him lying (or at least shading the truth).

Remember Martha Stewart!

DeLay. Frist. Rove. Talk about decapitations.

Let's Amend The Constitution To Ban Second Terms

Lyndon Johnson -- Vietnam

Richard Nixon -- Watergate

Ronald Reagan -- Iran-Contra

Bill Clinton -- Monica Lewinsky/Whitewater, etc.

I don't know what this says about our culture or politics or politicians or values, but it seems reasonably clear that we have reached the point at which 4 years is enough. For some, of course, even four years is too much (Ford, Carter, Bush I), but I guess we can't ban people from ever becoming President.

Monday, October 10, 2005

There's Always A Silver Lining

Saturday, October 08, 2005

Now That Is Really Harsh

As one astute American conservative commentator has already observed, President Bush has morphed into the Manchurian Candidate, behaving as if placed among Americans by their enemies to do them damage.How does a President -- or a Party -- recover from this kind of anger from within his/its own "base"?

FYI: The "astute American conservative commenter" is apparently Dana Blankenhorn at Corante.

Agony On The Right

Krauthammer and Kristol have both called for the Miers nomination to be withdrawn. Rush Limbaugh, George Will, and Laura Ingraham have expressed the gravest concern. Your ballots are running more than 15 to 1 against confirmation. (I will close the balloting at 5 pm Eastern Time today and post results tonight.)He ultimately concludes: "It would be best if this nomination were quietly and decently withdrawn. If not, it should be resisted."

But all this raises the question: What Now?

* * * *

The serious defense is offered by Hugh Hewitt: concern for the president's political position. Despite Kristol and Krauthammer's wise advice, President Bush will not voluntarily withdraw this nomination. That would be utterly out of character. So, as Hewitt argues,

"Continuing the assault on Miers means committing to her defeat...." And, according to Hewitt, a defeat of the Miers nomination by Republicans would be a self-destructive act.

These words need to be taken seriously. A Miers defeat, if it could be made to happen, would deal a serious blow to the Bush presidency. Conservatives need to think hard about that.

But Bush defenders like Hewitt need to consider this: A Miers win would also deal serious blows - to the Republican party, to the conservative movement, and, yes, to the Bush presidency.

Surfing around the web, it is awfully hard to find anyone apart from an Administration mouthpiece who has anything good to say about Miers. In today's NYT, John Tierney and Maureen Dowd both agree that the nomination is a mistake. Indeed, Tierny, the conservative, is actually more contemptuos than Dowd, which is always a hard thing to be. He opens his column, which is entitled "Justice Miers? Get Real" with the following:

The contrarian in me has been trying to find a reason to defend Harriet Miers against her critics, but it's too much of a stretch. We need a new nominee.Dowd finds herself in the unusual position of agreeing that "[t]he right is right about Ms. Miers's insufficiency to join the Brethren." But her native vindictiveness leads her to half hope Miers gets confirmed anyway:

Even if [Miers] was going to be a loyal conservative jurist before, why should she be now, after all the loathsome things [the Right has] said?Given what's going on here, I find it hard to see how Miers can make it.

The old maxim goes that a neoconservative is a liberal who got mugged by reality. But if you're a conservative mugged by conservatives, neo and paleo, it may have the opposite effect and turn you into ... David Souter!!!!

But what actually caught my attention in David Frum's piece was this statistic:

The president is down to 37% approval - but he still holds 80% of conservatives.Doesn't that mean that "conservatives" make up only 29.6% of the electorate? That is a pretty slim base on which to build a dynasty.

The 2006 elections are going to be interesting.

Friday, October 07, 2005

I Wonder What They Are Telling Themselves Now

Prayers had failed. Plan B called for a curse.Well, August 22 came and went and Sharon is still very much alive. I wonder what happened to the other guys. And, assuming at least some of them are still alive, aren't they feeling a bit embarrassed? Probably not, but it would be interesting to hear their explanation.

So a week ago, 20 men gathered in darkness around a grave in northern Israel to carry out the cabalist ritual pulsa denura , which in Aramaic means 'lash of fire.' The object of the curse was Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, who refuses to cancel his plan to evacuate 25 Jewish settlements in Palestinian territory.

According to participants, Sharon will be struck down by the Angels of Destruction in less than a month, or else the 20 men themselves will die.

Put To Shame By The Onion

If you doubt me, read this from The Onion: Evangelical Scientists Refute Gravity With New 'Intelligent Falling' Theory

Bush to the Right: She's OK. She's Born Again!

"A Republican strategist involved in the front lines of the battle for the Miers nomination, . . . said the White House plans to regain the upper hand by focusing on the nominee's conversion to evangelical Christianity. "Sometimes I just can't believe the things that come out of these peoples' mouths.

Caveat Emptor

"You'll sleep better if you remember that the truth is never simple, and that the first story you hear surely won't be the last."

Thursday, October 06, 2005

Roberts' First Big Case: The Oregon Death With Dignity Act

Washington Post

New York Times

LA Times

Chicago Tribune

Houston Chronicle

The Oregonian

Wichita Eagle (AP)

Slate.com

ProLifeBlogs.com

I do not pretend to have read all of these accounts yet. I do intend to, though, becuase I suspect there will be differences between the reports that will be interesting.

This is a case that fascinates me for a whole bunch of reasons:

First: It is one of those cases in which the "real" issue isn't actually before the court but nonetheless informs and influences everything the court does. The case is billed as a case about assisted suicide. And, at bottom, it really is. But technically, the only issue presented is whether John Ashcroft had the authority to "interpret" the CSA to bar prescription of controlled substances for purposes of assisted suicide. The Act itself doesn't address the issue, so the technical question is, given Congressional silence, who gets to decide: the feds or the states? But the answer to that question can never be divorced from the concrete implications. If the Court holds that it is the states who decide, then Oregon citizens, at least, will have the right to get physician assistance in committing suicide (under very controlled circumstances, of course) and there is significant potential that other states will follow Oregon's lead. If the Court rules that it is the feds that get to decide, then physician assisted suicide, at least via controlled substances, will be dead for the foreseeable future.

(As an aside, it is worth pointing out -- again -- the irony involved in a very conservative administration seeking to use federal statutes to limit state power. And, like the medical marijuana case, it is likely to result in the further irony that the Justices the Right so loves (Scalia and Thomas) are those most likely to rule against them while those they so hate (Stevens, Ginsburg, Souter) are the ones most likely to go with them. You see, in the end, it is the liberals on the Court who are in favor of broad federal power and it is the conservatives who believe in federalism.)

Second: The question of "who gets to decide" is a classic administratrive law question, and I am, and have been for nigh on 30 years now, an administrative lawyer. The process by which the court goes about resolving this issue and the criteria it uses to make its decision could well have implications for administrative law generally. For instance, in Chevron v. EPA, which is certainly the most important administrative law case in the last 25 years and one of the most important in history, the Court held that, where Congress has not spoken on a particular issue, the interpretation advanced by the federal agency charged with implementing the particular federal law at issue is entitled to "substantial deference," which effectiv ely means that the agency wins. In recent years, as the Court has become more conservative, it has backed away from Chevron a bit, holding that "Chevron deference" is appropriate only under certain circumtances; circumstances that arguably do not exist with regard to the Ascroft "interprative ruling" that lies at the core of Gonzales v. Oregon. Thus, there is some chance that Gonzales will either further erode Chevron or reaffirm the basic principle that the feds get to decide the close questions.

Third: The "real issue" -- to what extent should individuals have the right to make end-of-life decisions free from government interference -- is one I actually care about. Much more so that abortion, that right seem to me to be implicit in the liberty guarantees of the 5th and 14th Amendments, since, in the case of assissted suicide the "person" dying and the person deciding are one and the same. Unfortunately though, perhaps, the Supreme Court has already ruled that the Consitution's liberty guarantees to not create a right to assisted suicide. See Washington v. Glucksburg. However, since Glucksburg involved a State ban on assisted suicide, that case arguably leaves open the question of whether States can allow it, at least absent a clear federal prohibition. That is the issue presented in Gonzales.

Finally, and maybe most interesting of all: This is Chief Judge Roberts first "big" case, and it touches on all of the hot botton issues that he evaded so skillfully in his hearings: "right to life;" federalism (i.e. the power of the States vs the power of the feds); and the extent of the commerce clause (which provides the constituional basis for the CSA). Coming so early in his career as Chief Justice and so soon after his confirmation hearings, it will be fascinating to see how he himself rules and what he is able to do to sway the other members of the court.

I can hardly WAIT for the opinion.

Wednesday, October 05, 2005

Waiting For The Other Shoe(s) To Drop

Why exactly did Judy Miller decide to go to jail and then come out of jail? The Times promises full disclosure "soon", but in the meantime skepticism abounds. From Dan Froomkin's long article on the subject in today's WaPO :

So what was Miller doing in jail? Was it all just a misunderstanding? The most charitable explanation for Miller is that she somehow concluded that Libby wanted her to keep quiet, even while he was publicly -- and privately -- saying otherwise. The least charitable explanation is that going to jail was Miller's way of transforming herself from a journalistic outcast (based on her gullible pre-war reporting) into a much-celebrated hero of press freedom.The rest of the article makes clear that he is not buying "the charitable explnantion." Neither is Jay Rosen at Pressthink.